Eanna Inanna Sumer, Э-Ана, Инанна, Шумеры

"Eanna Inanna Sumer , Э-Ана, Инанна, Шумеры"

https://proza.ru/2021/12/27/670

http://stihi.ru/2021/12/27/2924

diary on line

дневник он лайн

27.12.2021. UK, Внликобритания, Ноттингемшире

diary on-line

Eanna Inanna Sumer , Э-Ана, Инанна, Шумеры

Please, not THAT while I am Miss Eanna Inna Balzina-Balzin

born as Inna Aleksandrovna Balzina and baptised as Irina Erina

that name "Inna" "Ina" (Enna, Ena), Inga, Ingrida (Enga, Engrida)

is a popular female name in Baltic region (Norway, ..., Latvia, ..., Poland)

The male name Ean is popular name in England writing similar Ioan Eoan Ean Eann

Please note, "England" and "land of Eng" , names Eng, Ing, or wife (wife, daugter, sister, mother of) Eng/Ing as Enga or Inga

working wor-king /work-ing

So, may be "England" name had some hidden roots connections to Sumer

and name of Eanna /Inanna old ancient temple point in Iraq

as Sumer culture spreaded widely in Turkey area which closed

and Irish old families came from Turkey some ancient settlements.

I say and i write "may be". May yes, may be not.

The names of ancients goddess had been noy sounding and some moved to an ordinary life

as names.

Really, old English male name was "Ean"

Females names with -e or -a on the end , Eanne or Eanna.

So, if to see the male name Ean in England

with a move to Sumer time place to find Eanna Temple (in Iraq) (from Sumer time).

I mean, old ancient names of Goddess, Gods, transformed in names.

So, we are humans, and some never knew they cared names of ancient old places/goddess/Sumer time.

------------------------------------

Notes

Ean

Eann

- the English name Ean

Ean

EAN

Ean

name of boy, a man

Origin: Scottish

Meaning: God is gracious

Ean

as a boy's name is of

Irish, Scottish, and Hebrew origin,

and the meaning of Ean is "God is gracious".

Popularity:2984

Similar Names

Ean

Eoin

Ian

Eian

Keenan

Aedan

Leon

Reno

Egan

Eamon

Gian

Enoch

Ethan

Dino

Edan

Zeno

Nino

Gino

Keon

Lino

Aeson

Ean - Baby Name Meaning, Origin and Popularity - TheBump ...

https://www.thebump.com/b/ean-baby-name

Ean

Etymology & Historical Origin of the Baby Name

Ean

Ean

is the Gaelic-Manx form of

John.

Other Gaelic forms of

John are

Sean (Irish) and

Ian (Scottish)

while the Welsh people use Evan.

But wait, who are the Manx people exactly?

They are the folks who live

on the Isle of Man

in the Irish Sea

between

Ireland and the United Kingdom.

Like Irish-Gaelic and Scottish-Gaelic,

Manx is another Celtic language

stemming from the Gaelic branch

(while Breton, Cornish and Welsh come from the Brythonic branch).

Although the Celts

date back to the Iron Age on the Isle of Man,

many Celtic Druids from Britannia

found shelter there during the Roman occupation of England in the first centuries A.D.

Later in the 5th century, Gaels from Ireland, mostly Christian missionaries, brought the Gaelic branch of the Celtic language to the island, and from there the Manx-Gaelic language developed in isolation (which is why it’s distinctly different than the Irish or Scottish-Gaelic languages).

You can see how close the Manx Ean is to the Scottish Ian

– which became ethnic forms of John in their own native tongue.

The name John was popularized throughout the British Isles after the Crusades

(a series of religious wars between the 11th and 13th centuries).

Many Christian knights and peasants throughout Western Europe made their way east to the Holy Lands in order to restore Christian access to the sacred city of Jerusalem and to liberate the Eastern Christians from invading and occupying Turkish Sunni Muslims.

When the so-called pilgrim-warriors returned home from their crusades reinvigorated by their faith, they brought the Biblical name John back to England (anglicized from the Hebrew Yochanan and the Greek Ioannes meaning “God is gracious”).

From that point on, there was no stopping the popularity of this name throughout Western Europe – and every language had their own version of the name.

It was the Manx people we can thank for giving us Ean.

Popularity

OF THE BOY NAME EAN

We’re not quite sure who discovered this little Manx charmer, but Ean first appeared on the U.S. male naming charts in 1999. Compared to other Celtic forms of John (Sean, Ian, Evan), Ean is a distant favorite. Because so few people are even aware of the history and culture of the Manx people or even the location of the Isle of Man, we have to assume Ean was introduced to American parents merely as a phonetically altered form of Ian. In fact, we think Manx people pronounce Ean as EEN whereas Americans would say EE-an. Regardless how Ean found his way to the Top 1000 list, we find the background interesting. If you are a lover of Celtic culture and names, then Ean would be an unusual and original choice. American Idol runner-up Bo Bice would agree; he named his third son Ean Jacob in 2010.

Famous People

NAMED EAN

Ean Evans (former bassist for Lynyrd Skynyrd)

Historic Figures

WITH THE NAME EAN

We cannot find any historically significant people with the first name Ean

*** They had not looked in Sumer for Eanna and Inanna

All baby names: Ean

https://ohbabynames.com/all-baby-names/ean/

All Baby name: Ean

https://ohbabynames.com/all-baby-names/ean/

-------------------------------------

Notes

Ean

Ian

Ean

Ian

International Article Number originally :

European Article Number

The International Article Number is a standard describing a barcode symbology and numbering system used in global trade to identify a specific retail product type, in a specific packaging configuration, from a specific manufacturer. Wikipedia

European Article numbering code (EAN) is a series of letters and numbers in a unique order that helps identify specific products within your own .

------------------------------------------------------

My note

Ean Ин Э-ан

ean

air

Home Ean Ave Aven

Heaven Хэвен Рай (Дом Иэн)

-----------------------------------

Notes

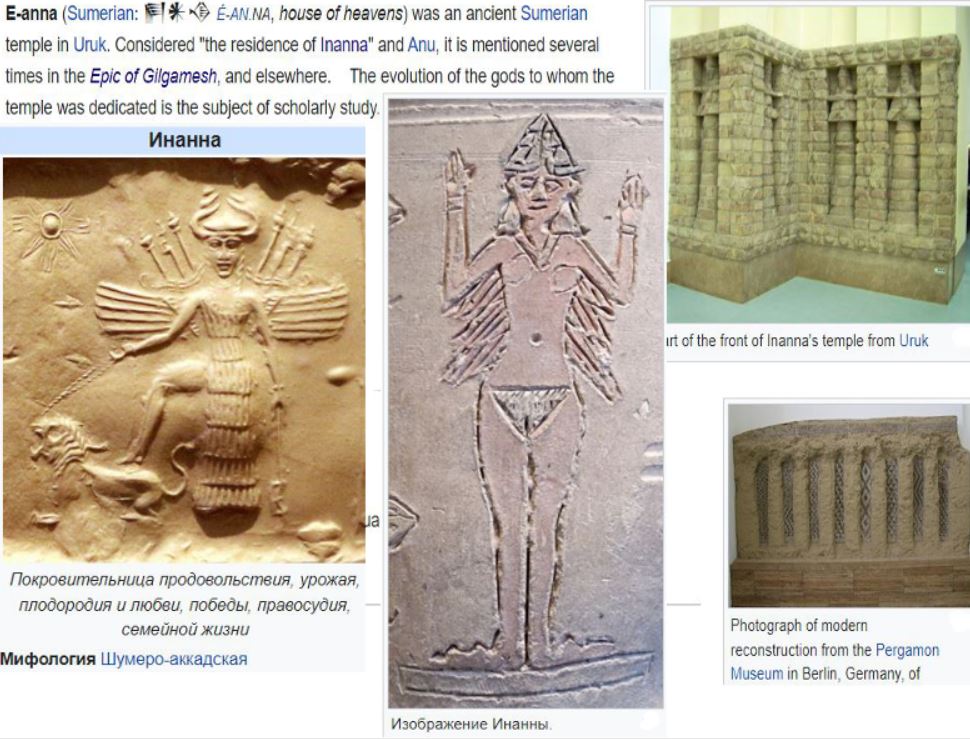

From Wikipedia - a Free Enciclopedia

EANNA

INANNA

Eanna - Wikipedia

Eanna

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eanna

E-anna was an ancient Sumerian temple in Uruk. Considered "the residence of Inanna" and Anu, it is mentioned several times in the Epic of Gilgamesh, ...

Inanna - Wikipedia

Inanna

https://en.wikipedia.org › wiki › Inanna

Inanna is an ancient Mesopotamian goddess associated with love, beauty, sex, war, justice and political power. She was originally worshiped in Sumer under ...

Eanna

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eanna

Inanna

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inanna

EANNA

E-anna

Sumerian: E-AN.NA, "house of heavens"

was

an ancient Sumerian temple in Uruk.

Considered

"the residence of Inanna" and Anu,

it is mentioned several times

in the Epic of Gilgamesh,

and elsewhere.

The evolution of the gods

to whom the temple

was dedicated is the subject of scholarly study.

The Epic of Gilgamesh

From Tablet One:

"He carved on a stone stela all of his toils,

and built the wall of Uruk-Haven,

the wall of the sacred Eanna Temple, the holy sanctuary."

See also

Uruk - Eanna district

References

Jeffrey H. Tigay (1982). The Evolution of the Gilgamesh Epic.

Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers. ISBN 9780865165465.

"Epic of Gilgamesh: Tablet I".

Photos

Part of the front of Inanna's temple from Uruk

Photograph of modern reconstruction from the Pergamon Museum in Berlin, Germany, of columns with decorative clay pins resembling mosaics from the Eanna temple

---------------------------------------------------------

Inanna

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

---------------------------------------------------------

Inanna

Inanna/Ishtar

Queen of Heaven

Goddess of sex, love, war, justice, and political power

Goddess

Ishtar

on an Akkadian Empire seal, 2350–2150 BCE.

She is equipped with weapons on her back,

has a horned helmet, and is trampling a lion held on a leash.

Major cult center

Uruk; Agade; Nineveh

Abode Heaven

Planet Venus

Symbol

hook-shaped knot of reeds, eight-pointed star (snowdrop), lion, rosette, dove

Mount Lion

-------------------------------------------------------

Personal information

-----------------------------------------------------------

Parents

most common tradition:

Nanna and

Ningal

-----------------------------------------------------------

Possible alternate tradition:

An

and an unknown mother

In some literary works: possibly

Enlil and an unknown mother

or

Enki and an unknown mother

----------------------------------------------

Siblings

Utu/Shamash (twin brother)

in Inanna's Descent:

Ereshkigal (older sister)

In some neo-Assyrian sources:

Hadad (brother)

-------------------------------------------

Consort

Dumuzid the Shepherd;

Zababa;

many unnamed others

---------------------------------------------

Children

usually none, but rarely

Lulal and/or Shara or Nanaya

-------------------------------------------------

--------------------------

Equivalents:

---------------------------

Inanna

Ishtar

Greek equivalent Aphrodite, Athena

Roman equivalent Venus, Minerva

Canaanite equivalent Astarte

Elamite equivalent Pinikir

Hurrian equivalent Shaushka

Inanna

Inanna

is an ancient Mesopotamian goddess associated with love, beauty, sex, war, justice and political power.

She was originally worshiped in Sumer under the name "Inanna",

and was later worshipped

by the Akkadians, Babylonians, and Assyrians under the name Ishtar.

She was known as the "Queen of Heaven"

and was the patron goddess of the Eanna temple at the city of Uruk [in Iraque],

which was her main cult center.

She was associated with the planet Venus

and her most prominent symbols included the lion and the eight-pointed star.

Her husband was the god Dumuzid

(later known as Tammuz)

and her sukkal, or personal attendant,

was the goddess Ninshubur

(who later became conflated with the male deities Ilabrat and Papsukkal).

Inanna was worshiped in Sumer

at least as early as

the Uruk period

(c. 4000 BCE – c. 3100 BCE),

but

she had little cult activity before

the conquest of Sargon of Akkad.

During the post-Sargonic era, she became one of the most widely venerated deities in the Sumerian pantheon, with temples across Mesopotamia.

The cult of Inanna/Ishtar,

which may have been associated with a variety of sexual rites, was continued

by the East Semitic-speaking people

(Akkadians, Assyrians and Babylonians)

who succeeded and absorbed the Sumerians in the region.

She was especially beloved by the Assyrians,

who elevated her to become the highest deity in their pantheon,

ranking above their own national god Ashur.

Inanna/Ishtar

is alluded to in the Hebrew Bible

and she greatly influenced the Ugaritic Ashtart

and later Phoenician Astarte,

who in turn possibly influenced the development

of the Greek goddess Aphrodite.

Her cult continued to flourish until its gradual decline

between the first and sixth centuries CE

in the wake of Christianity.

Inanna appears in more myths than any other Sumerian deity.

She also had a uniquely high number of epithets and alternate names,

comparable only to Nergal.

Many of her myths involve her taking over the domains of other deities.

She was believed to have been given the mes, which represented all positive and negative aspects of civilization, by Enki, the god of wisdom.

She was also believed to have taken over the Eanna temple from An, the god of the sky.

Alongside her twin brother Utu (later known as Shamash), Inanna was the enforcer of divine justice; she destroyed Mount Ebih for having challenged her authority,

unleashed her fury

upon the gardener Shukaletuda

after he raped her in her sleep,

and tracked down the bandit woman Bilulu

and killed her in divine retribution for having murdered Dumuzid.

In the standard Akkadian version of the Epic of Gilgamesh,

Ishtar asks Gilgamesh

to become her consort.

When he refuses,

she unleashes the Bull of Heaven,

resulting in the death of Enkidu

and Gilgamesh's subsequent grapple with his mortality.

Inanna/Ishtar's most famous myth

is the story of her descent into and return from Kur,

the Ancient Mesopotamian underworld,

a myth

in which she attempts to conquer

the domain of

her older sister Ereshkigal, the queen of the underworld,

but is instead deemed guilty by the seven judges of the underworld and struck dead.

Three days later, Ninshubur pleads with all the gods to bring Inanna back, but all of them refuse her except Enki, who sends two sexless beings to rescue Inanna.

They escort Inanna out of the underworld, but the galla, the guardians of the underworld, drag her husband Dumuzid down to the Underworld as her replacement.

Dumuzid is eventually permitted to return to heaven for half the year while his sister Geshtinanna remains in the underworld for the other half, resulting in the cycle of the seasons.

Etymology

Inanna receiving offerings on the Uruk Vase, circa 3200-3000 BCE.

Inanna and Ishtar were originally separate, unrelated deities,[14][3][15][16] but they were equated with each other during the reign of Sargon of Akkad and came to be regarded as effectively the same goddess under two different names.[14][3][15][16] Inanna's name may derive from the Sumerian phrase nin-an-ak, meaning "Lady of Heaven",[17][18] but the cuneiform sign for Inanna (;) is not a ligature of the signs lady (Sumerian: nin; Cuneiform: ;; SAL.TUG2) and sky (Sumerian: an; Cuneiform: ; AN).[18][17][19] These difficulties led some early Assyriologists to suggest that Inanna may have originally been a Proto-Euphratean goddess, who was only later accepted into the Sumerian pantheon. This idea was supported by Inanna's youthfulness, as well as the fact that, unlike the other Sumerian divinities, she seems to have initially lacked a distinct sphere of responsibilities.[18] The view that there was a Proto-Euphratean substrate language in Southern Iraq before Sumerian is not widely accepted by modern Assyriologists.[20]

The name Ishtar occurs as an element in personal names from both the pre-Sargonic and post-Sargonic eras in Akkad, Assyria, and Babylonia.[21] It is of Semitic derivation[22][21] and is probably etymologically related to the name of the West Semitic god Attar, who is mentioned in later inscriptions from Ugarit and southern Arabia.[22][21] The morning star may have been conceived as a male deity who presided over the arts of war and the evening star may have been conceived as a female deity who presided over the arts of love.[21] Among the Akkadians, Assyrians, and Babylonians, the name of the male god eventually supplanted the name of his female counterpart,[16] but, due to extensive syncretism with Inanna, the deity remained as female, although her name was in the masculine form.[16]

Origins and development

The Uruk Vase (Warka Vase), depicting votive offerings to Inanna (3200-3000 BCE).[23]

Inanna has posed a problem for many scholars of ancient Sumer due to the fact that her sphere of power contained more distinct and contradictory aspects than that of any other deity.[24] Two major theories regarding her origins have been proposed.[25] The first explanation holds that Inanna is the result of a syncretism between several previously unrelated Sumerian deities with totally different domains.[25] The second explanation holds that Inanna was originally a Semitic deity who entered the Sumerian pantheon after it was already fully structured, and who took on all the roles that had not yet been assigned to other deities.[26]

As early as the Uruk period (c. 4000 – c. 3100 BCE), Inanna was already associated with the city of Uruk.[3] During this period, the symbol of a ring-headed doorpost was closely associated with Inanna.[3] The famous Uruk Vase (found in a deposit of cult objects of the Uruk III period) depicts a row of naked men carrying various objects, including bowls, vessels, and baskets of farm products,[27] and bringing sheep and goats to a female figure facing the ruler.[28] The female stands in front of Inanna's symbol of the two twisted reeds of the doorpost,[28] while the male figure holds a box and stack of bowls, the later cuneiform sign signifying the En, or high priest of the temple.[29]

Seal impressions from the Jemdet Nasr period (c. 3100 – c. 2900 BCE) show a fixed sequence of symbols representing various cities, including those of Ur, Larsa, Zabalam, Urum, Arina, and probably Kesh.[30] This list probably reflects the report of contributions to Inanna at Uruk from cities supporting her cult.[30] A large number of similar seals have been discovered from phase I of the Early Dynastic period (c. 2900 – c. 2350 BCE) at Ur, in a slightly different order, combined with the rosette symbol of Inanna.[30] These seals were used to lock storerooms to preserve materials set aside for her cult.[30]

Various inscriptions in the name of Inanna are known, such as a bead in the name of King Aga of Kish circa 2600 BCE, or a tablet by King Lugal-kisalsi circa 2400 BCE:

BM 91013 Tablet dedicated by Lugal-tarsi.jpg

"For An, king of all the lands, and for Inanna, his mistress, Lugal-kisalsi, king of Kish, built the wall of the courtyard."

—;Inscription of Lugal-kisalsi.[31]

During the Akkadian period (c.;2334 – 2154 BCE), following the conquests of Sargon of Akkad, Inanna and originally independent Ishtar became so extensively syncretized that they became regarded as effectively the same.[14][16] The Akkadian poet Enheduanna, the daughter of Sargon, wrote numerous hymns to Inanna, identifying her with Ishtar.[14][32] Sargon himself proclaimed Inanna and An as the sources of his authority.[33] As a result of this,[14] the popularity of Inanna/Ishtar's cult skyrocketed.[14][3][15] Alfonso Archi, who was involved in early excavations of Ebla, assumes Ishtar was originally a goddess venerated in the Euphrates valley, pointing out that an association between her and the desert poplar is attested in the most ancient texts from both Ebla and Mari. He considers her, a moon god (e.g. Sin) and a sun deity of varying gender (Shamash/Shapash) to be the only deities shared between various early Semitic peoples of Mesopotamia and ancient Syria, who otherwise had different not necessarily overlapping pantheons.[34]

Worship

Inanna's symbol: the reed ring-post

Emblem of goddess Inanna, circa 3000 BCE.[36]

Ring posts of Inanna on each side of a temple door, with naked devotee offering libations.[35]

On the Warka Vase

Cuneiform logogram "Inanna"

Inanna's symbol is a ring post made of reed, an ubiquitous building material in Sumer. It was often beribboned and positionned at the entrance of temples, and marked the limit between the profane and the sacred realms.[35] The design of the emblem was simplified between 3000-2000 BCE to become the cuneiform logogram for Inanna: ;, generally preceded by the symbol for "deity" ;.[17]

Ancient Sumerian statuette of two gala priests, dating to c. 2450 BCE, found in the temple of Inanna at Mari

Gwendolyn Leick assumes that during the Pre-Sargonic era, the cult of Inanna was rather limited,[14] though other experts argue that she was already the most prominent deity in Uruk and a number of other political centers in the Uruk period.[37] [12][19][9] She had temples in Nippur, Lagash, Shuruppak, Zabalam, and Ur,[14] but her main cult center was the Eanna temple in Uruk,[14][38][18][c] whose name means "House of Heaven" (Sumerian: e2-anna; Cuneiform: ;; E2.AN).[d] Some researches assume that the original patron deity of this fourth-millennium BCE city was An.[18] After its dedication to Inanna, the temple seems to have housed priestesses of the goddess.[18] Next to Uruk, Zabalam was the most important early site of Inanna worship, as the name of the city was commonly written with the signs MUs3 and UNUG, meaning respectively "Inanna" and "sanctuary."[40] It's possible that the city goddess of Zabalam was originally a distinct deity, though one whose cult was absorbed by that of the Urukean goddess very early on.[40] Joan Goodnick Westenholz proposed that a goddess identified by the name Nin-UM (reading and meaning uncertain), associated with Ishtaran in a zame hymn, was the original identity of Inanna of Zabalam.[41]

In the Old Akkadian period, Inanna merged with the Akkadian goddess Ishtar, associated with the city of Agade.[42] A hymn from that period addresses the Akkadian Ishtar as "Inanna of the Ulmas" alongside Inanna of Uruk and of Zabalam.[42] The worship of Ishtar and syncretism between her and Inanna was encouraged by Sargon and his successors,[42] and as a result she quickly became one of the most widely venerated deities in the Mesopotamian pantheon.[14] In inscriptions of Sargon, Naram-Sin and Shar-Kali-Sharri Ishtar is the most frequently invoked deity.[43]

In the Old Babylonian period, her main cult centers were, in addition to aforementioned Uruk, Zabalam and Agade, also Ilip.[44] Her cult was also introduced from Uruk to Kish.[45]

During later times, while her cult in Uruk continued to flourish,[46] Ishtar also became particularly worshipped in the Upper Mesopotamian kingdom of Assyria (modern northern Iraq, northeast Syria and southeast Turkey), especially in the cities of Nineveh, Assur and Arbela (modern Erbil).[47] During the reign of the Assyrian king Assurbanipal, Ishtar rose to become the most important and widely venerated deity in the Assyrian pantheon, surpassing even the Assyrian national god Ashur.[46] Votive objects found in her primary Assyrian temple indicate that she was a popular deity among women.[48]

Individuals who went against the traditional gender binary were heavily involved in the cult of Inanna.[49] During Sumerian times, a set of priests known as gala worked in Inanna's temples, where they performed elegies and lamentations.[50] Men who became gala sometimes adopted female names and their songs were composed in the Sumerian eme-sal dialect, which, in literary texts, is normally reserved for the speech of female characters. Some Sumerian proverbs seem to suggest that gala had a reputation for engaging in anal sex with men.[51] During the Akkadian Period, kurgarr; and assinnu were servants of Ishtar who dressed in female clothing and performed war dances in Ishtar's temples.[52] Several Akkadian proverbs seem to suggest that they may have also had homosexual proclivities.[52] Gwendolyn Leick, an anthropologist known for her writings on Mesopotamia, has compared these individuals to the contemporary Indian hijra.[53] In one Akkadian hymn, Ishtar is described as transforming men into women.[54]

According to the early scholar Samuel Noah Kramer, towards the end of the third millennium BCE, kings of Uruk may have established their legitimacy by taking on the role of the shepherd Dumuzid, Inanna's consort.[55] This ritual lasted for one night on the tenth day of the Akitu,[55][56] the Sumerian new year festival,[56] which was celebrated annually at the spring equinox.[55] The king would then partake in a "sacred marriage" ceremony,[55] during which he engaged in ritual sexual intercourse with the high priestess of Inanna, who took on the role of the goddess.[55][56] In the late twentieth century, the historicity of the sacred marriage ritual was treated by scholars as more-or-less an established fact,[57] but, largely due to the writings of Pirjo Lapinkivi, many have begun to regard the sacred marriage as a literary invention rather than an actual ritual.[57]

The cult of Ishtar was long thought to have involved sacred prostitution,[58][59][47][60] but this is now rejected among many scholars.[61][62][63][64] Hierodules known as ishtaritum are reported to have worked in Ishtar's temples,[59] but it is unclear if such priestesses actually performed any sex acts[62] and several modern scholars have argued that they did not.[63][61] Women across the ancient Near East worshipped Ishtar by dedicating to her cakes baked in ashes (known as kam;n tumri).[65] A dedication of this type is described in an Akkadian hymn.[66] Several clay cake molds discovered at Mari are shaped like naked women with large hips clutching their breasts.[66] Some scholars have suggested that the cakes made from these molds were intended as representations of Ishtar herself.[67]

Iconography

Symbols

The eight-pointed star was Inanna/Ishtar's most common symbol.[68][69] Here it is shown alongside the solar disk of her brother Shamash (Sumerian Utu) and the crescent moon of her father Sin (Sumerian Nanna) on a boundary stone of Meli-Shipak II, dating to the twelfth century BCE.

Lions were one of Inanna/Ishtar's primary symbols.[70][71] The lion above comes from the Ishtar Gate, the eighth gate to the inner city of Babylon, which was constructed in around 575 BCE under the orders of Nebuchadnezzar II.[72]

Inanna/Ishtar's most common symbol was the eight-pointed star,[68] though the exact number of points sometimes varies.[69] Six-pointed stars also occur frequently, but their symbolic meaning is unknown.[73] The eight-pointed star seems to have originally borne a general association with the heavens,[74] but, by the Old Babylonian Period (c. 1830 – c. 1531 BCE), it had come to be specifically associated with the planet Venus, with which Ishtar was identified.[74] Starting during this same period, the star of Ishtar was normally enclosed within a circular disc.[73] During later Babylonian times, slaves who worked in Ishtar's temples were sometimes branded with the seal of the eight-pointed star.[73][75] On boundary stones and cylinder seals, the eight-pointed star is sometimes shown alongside the crescent moon, which was the symbol of Sin (Sumerian Nanna) and the rayed solar disk, which was a symbol of Shamash (Sumerian Utu).[69]

Inanna's cuneiform ideogram was a hook-shaped twisted knot of reeds, representing the doorpost of the storehouse, a common symbol of fertility and plenty.[76] The rosette was another important symbol of Inanna, which continued to be used as a symbol of Ishtar after their syncretism.[77] During the Neo-Assyrian Period (911 – 609 BCE), the rosette may have actually eclipsed the eight-pointed star and become Ishtar's primary symbol.[78] The temple of Ishtar in the city of Assur was adorned with numerous rosettes.[77]

Inanna/Ishtar was associated with lions,[70][71] which the ancient Mesopotamians regarded as a symbol of power.[70] Her associations with lions began during Sumerian times;[71] a chlorite bowl from the temple of Inanna at Nippur depicts a large feline battling a giant snake and a cuneiform inscription on the bowl reads "Inanna and the Serpent", indicating that the cat is supposed to represent the goddess.[71] During the Akkadian Period, Ishtar was frequently depicted as a heavily armed warrior goddess with a lion as one of her attributes.[79]

Doves were also prominent animal symbols associated with Inanna/Ishtar.[80][81] Doves are shown on cultic objects associated with Inanna as early as the beginning of the third millennium BCE.[81] Lead dove figurines were discovered in the temple of Ishtar at Assur, dating to the thirteenth century BCE[81] and a painted fresco from Mari, Syria shows a giant dove emerging from a palm tree in the temple of Ishtar,[80] indicating that the goddess herself was sometimes believed to take the form of a dove.[80]

As the planet Venus

Inanna was associated with the planet Venus, which is named after her Roman equivalent Venus.[38][82][38] Several hymns praise Inanna in her role as the goddess or personification of the planet Venus.[83] Theology professor Jeffrey Cooley has argued that, in many myths, Inanna's movements may correspond with the movements of the planet Venus in the sky.[83] In Inanna's Descent to the Underworld, unlike any other deity, Inanna is able to descend into the netherworld and return to the heavens. The planet Venus appears to make a similar descent, setting in the West and then rising again in the East.[83] An introductory hymn describes Inanna leaving the heavens and heading for Kur, what could be presumed to be the mountains, replicating the rising and setting of Inanna to the West.[83] In Inanna and Shukaletuda, Shukaletuda is described as scanning the heavens in search of Inanna, possibly searching the eastern and western horizons.[84] In the same myth, while searching for her attacker, Inanna herself makes several movements that correspond with the movements of Venus in the sky.[83]

Because the movements of Venus appear to be discontinuous (it disappears due to its proximity to the sun, for many days at a time, and then reappears on the other horizon), some cultures did not recognize Venus as a single entity;[83] instead, they assumed it to be two separate stars on each horizon: the morning and evening star.[83] Nonetheless, a cylinder seal from the Jemdet Nasr period indicates that the ancient Sumerians knew that the morning and evening stars were the same celestial object.[83] The discontinuous movements of Venus relate to both mythology as well as Inanna's dual nature.[83]

Modern astrologers recognize the story of Inanna's descent into the underworld as a reference to an astronomical phenomenon associated with retrograde Venus. Seven days before retrograde Venus makes its inferior conjunction with the sun, it disappears from the evening sky. The seven day period between this disappearance and the conjunction itself is seen as the astronomical phenomenon on which the myth of descent was based. After the conjunction, seven more days elapse before Venus appears as the morning star, corresponding to the ascent from the underworld.[85][86]

Inanna in her aspect as Anun;tu was associated with the eastern fish of the last of the zodiacal constellations, Pisces.[87][88] Her consort Dumuzi was associated with the contiguous first constellation, Aries.[87]

Babylonian terracotta relief of Ishtar from Eshnunna (early second millennium BCE)

Life-sized statue of a goddess, probably Ishtar, holding a vase from Mari, Syria (eighteenth century BC)

Terracotta relief of Ishtar with wings from Larsa (second millennium BCE)

Stele showing Ishtar holding a bow from Ennigaldi-Nanna's museum (eighth century BCE)

Hellenized bas-relief sculpture of Ishtar standing with her servant from Palmyra (third century CE)

Character

Ancient Akkadian cylinder seal depicting Inanna resting her foot on the back of a lion while Ninshubur stands in front of her paying obeisance, c. 2334 – c. 2154 BCE[89]

The Sumerians worshipped Inanna as the goddess of both warfare and love.[3] Unlike other gods, whose roles were static and whose domains were limited, the stories of Inanna describe her as moving from conquest to conquest.[24][90] She was portrayed as young and impetuous, constantly striving for more power than she had been allotted.[24][90]

Although she was worshipped as the goddess of love, Inanna was not the goddess of marriage, nor was she ever viewed as a mother goddess.[91][92] Andrew R. George goes as far as stating that "According to all mythology, Istar was not(...) temperamentally disposed" towards such functions.[93] As noted by Joan Goodnick Westenholz, it has even been proposed that Inanna was significant specifically because she was not a mother goddess.[94] As a love goddess, she was commonly invoked in incantations.[95]

In Inanna's Descent to the Underworld, Inanna treats her lover Dumuzid in a very capricious manner.[91] This aspect of Inanna's personality is emphasized in the later standard Akkadian version of the Epic of Gilgamesh in which Gilgamesh points out Ishtar's infamous ill-treatment of her lovers.[96][97] However, according to assyriologist Dina Katz, the portrayal of Inanna's relationship with Dumuzi in the Descent myth is unusual.[98][99]

Inanna was also worshipped as one of the Sumerian war deities.[38][100] One of the hymns dedicated to her declares: "She stirs confusion and chaos against those who are disobedient to her, speeding carnage and inciting the devastating flood, clothed in terrifying radiance. It is her game to speed conflict and battle, untiring, strapping on her sandals."[101] Battle itself was occasionally referred to as the "Dance of Inanna".[102] Epithets related to lions in particular were meant to highlight this aspect of her character.[103] As a war goddess she was sometimes referred to with the name Irnina ("victory"),[104] though this epithet could be applied to other deities as well,[105][106][107] in addition to functioning as a distinct goddess linked to Ningishzida[108] rather than Ishtar. Another epithet highlighting this aspect of Ishtar's nature was Anunitu ("the martial one").[109] Like Irnina, Anunitu could also be a separate deity,[110] and as such she is first attested in documents from the Ur III period.[111]

Assyrian royal curse formulas invoked both of Ishtar's primary functions at once, invoking her to remove potency and martial valor alike.[112] Mesopotamian texts indicate that traits perceived as heroic, such as a king's ability to lead his troops and to triumph over enemies, and sexual prowess were regarded as interconnected.[113]

While Inanna/Ishtar was a goddess, her gender could be ambiguous at times.[114] Gary Beckman states that "ambiguous gender identification" was a characteristic not just of Ishtar herself but of a category of deities he refers to as "Ishtar type" goddesses (ex. Shaushka, Pinikir or Ninsianna).[115] A late hymn contains the phrase "she [Ishtar] is Enlil, she is Ninil" which might be a reference to occasionally "dimorphic" character of Ishtar, in addition to serving as an exaltation.[116] A hymn to Nanaya alludes to a male aspect of Ishtar from Babylon alongside a variety of more standard descriptions.[117] However, Illona Zsonlany only describes Ishtar as a "feminine figure who performed a masculine role" in certain contexts, for example as a war deity.[118]

Family

The marriage of Inanna and Dumuzid

An ancient Sumerian depiction of the marriage of Inanna and Dumuzid[119]

Inanna's twin brother was Utu (known as Shamash in Akkadian), the god of the sun and justice .[120][121][122] In Sumerian texts, Inanna and Utu are shown as extremely close;[123] some modern authors perceive their relationship as bordering on incestuous.[123][124] In the myth of her descent into the underworld, Inanna addresses Ereshkigal, the queen of the underworld, as her "older sister",[125][126] but the two goddesses almost never appear together in Sumerian literature[126] and weren't placed in the same category in god lists.[127] Due to Hurrian influence, in some neo-Assyrian sources (for example penalty clauses) Ishtar was also associated with Adad, with the relationship mirroring that between Shaushka and her brother Teshub in Hurrian mythology.[128]

The most common tradition regarded Nanna and his wife Ningal as her parents.[1][2] Examples of it are present in sources as diverse as a god list from the Early Dynastic period,[129] a hymn of Ishme-Dagan relaying how Enlil and Ninlil bestowed Inanna's powers upon her,[130] a late syncretic hymn to Nanaya,[131] and an Akkadian ritual from Hattusa.[132] While some authors assert that in Uruk Inanna was usually regarded as the daughter of the sky god An,[3][4] it's possible references to him as her father are only referring to his status as an ancestor of Nanna and thus his daughter.[2] In literary texts, Enlil[3][4] or Enki may be addressed as her fathers[3][4] but references to major gods being "fathers" can also be examples of the use of this word as an epithet indicating seniority.[94]

Dumuzid (later known as Tammuz), the god of shepherds, is usually described as Inanna's husband,[121] but according to some interpretations Inanna's loyalty to him is questionable;[3] in the myth of her descent into the Underworld, she abandons Dumuzid and permits the galla demons to drag him down into the underworld as her replacement.[133][134] In a different myth, The Return of Dumuzid Inanna instead mourns over Dumuzid's death and ultimately decrees that he will be allowed to return to Heaven to be with her for one half of the year.[135][134] Dina Katz notes that the portrayal of their relationship in Inanna's Descent is unusual;[99] it doesn't resemble the portrayal of their relationship in other myths about Dumuzi's death, which almost never pin the blame for it on Inanna, but rather on demons or even human bandits.[98] A large corpus of love poetry describing encounters between Inanna and Dumuzi has been assembled by researchers.[136] However, local manifestations of Inanna/Ishtar weren't necessarily associated with Dumuzi.[137] In Kish, the tutelary deity of the city, Zababa (a war god), was viewed as the consort of a local hyposthasis of Ishtar,[138] though after the Old Babylonian period Bau, introduced from Lagash, became his spouse (an example of a couple consisting out of a warrior god and a medicine goddess, common in Mesopotamian mythology[139]) and Ishtar of Kish started to instead be worshiped on her own.[138]

Inanna is not usually described as having any offspring,[3] but, in the myth of Lugalbanda and in a single building inscription from the Third Dynasty of Ur (c. 2112 – c. 2004 BCE), the warrior god Shara is described as her son.[140] She was also sometimes considered the mother of Lulal,[141] who is described in other texts as the son of Ninsun.[141] Wilfred G. Lambert described the relation between Inanna and Lulal as "close but unspecified" in the context of Inanna's Descent.[142]There is also similarly scarce evidence for the love goddess Nanaya being regarded as her daughter (a song, a votive formula and an oath), but it's possible all of these instances merely refer to an epithet indicating closeness between the deities and weren't a statement about actual parentage.[143]

Sukkal

Main article: Ninshubur

Inanna's sukkal was the goddess Ninshubur,[144] whose relationship with Inanna is one of mutual devotion.[144] In some texts, Ninshubur was listed right after Dumuzi as a member of Inanna's circle, even before some of her relatives;[145] in one text the phrase "Ninshubur, beloved vizier" appears.[145] In another text Ninshubur is listed even before Nanaya, originally possibly a hyposthasis of Inanna herself,[146] in a list of deities from her entourage.[147] In an Akkadian ritual text known from Hittite archives Ishtar's sukkal is invoked alongside her family members (Sin, Ningal and Shamash).[148]

Other members of Inanna's entourage frequently listed in god lists were the goddesses Nanaya (usually placed right behind Dumuzi and Ninshubur), Kanisurra, Gazbaba and Bizila, all of them also associated with each other in various configurations independently from this context.[147][149]

Syncretism and influence on other deities

In addition to the full conflation of Inanna and Ishtar during the reign of Sargon and his successors,[42] she was syncretised with a large number of deities[150] to a varying degree. The oldest known syncretic hymn is dedicated to Inanna,[151] and has been dated to the Early Dynastic period.[152] Many god lists compiled by ancient scribes contained entire "Inanna group" sections enumerating similar goddesses,[153] and tablet IV of the monumental god list An-Anum (7 tablets total) is known as the "Ishtar tablet" due to most of its contents being the names of Ishtar's equivalents, her titles and various attendants.[154] Some modern researchers use the term Ishtar-type to define specific figures of this variety.[155][132] Some texts contained references to "all the Ishtars" of a given area.[156]

In later periods Ishtar's name was sometimes used as a generic term ("goddess") in Babylonia, while a logographic writing of Inanna was used to spell the title B;ltu, leading to further conflations.[157] A possible example of such use of the name is also known from Elam, as a single Elamite inscription written in Akkadian refers to "Manzat-Ishtar," which might in this context mean "the goddess Manzat."[158]

Specific examples

Ashtart: in cities like Mari and Ebla, the Eastern and Western Semitic forms of the name (Ishtar and Ashtart) were regarded as basically interchangeable.[159] However, the western goddess evidently lacked the astral character of Mesopotamian Ishtar.[160] Ugaritic god lists and ritual texts equate the local Ashtart with both Ishtar and Hurrian Ishara.[161]

Ishara: due to association with Ishtar,[162] the Syrian goddess Ishara started to be regarded as a "lady of love" like her (and Nanaya) in Mesopotamia.[163][146] However, in Hurro-Hittite context Ishara was associated with the underworld goddess Allani instead and additionally functioned as a goddess of oaths.[163][164]

Nanaya: a goddess uniquely closely linked to Inanna, as according to assyriologist Frans Wiggermann her name was originally an epithet of Inanna (possibly serving as an appellative, "My Inanna!").[146] Nanaya was associated with erotic love, but she eventually developed a warlike aspect of her own too ("Nanaya Eursaba").[165] In Larsa Inanna's functions were effectively split between three separate figures and she was worshiped as part of a trinity consisting out of herself, Nanaya (as a love goddess) and Ninsianna (as an astral goddess).[166] Inanna/Ishtar and Nanaya were often accidentally or intentionally conflated in poetry.[167]

Ninegal: while she was initially an independent figure, starting with Old Babylonian period in some texts "Ninegal" is used as a title of Inanna, and in god lists she was a part of the "Inanna group" usually alongside Ninsianna.[168] An example of the usage of "Ninegal" as an epithet can be found in the text designated as Hymn to Inana as Ninegala (Inana D) in the ETCSL.

Ninisina: a special case of syncretism was that between the medicine goddess Ninisina and Inanna, which occurred for political reasons.[169] Isin at one point lost control over Uruk and identification of its tutelary goddess with Inanna (complete with assigning a similar warlike character to her), who served as a source of royal power, was likely meant to serve as a theological solution of this problem.[169] As a result, in a number of sources Ninisina was regarded as analogous to similarly named Ninsianna, treated as a manifestation of Inanna.[169] It's also possible that a ceremony of "sacred marriage" between Ninisina and the king of Isin had been performed as a result.[170]

Ninsianna: a Venus deity of varying gender.[171] Ninsianna was referred to as male by Rim-Sin of Larsa (who specifically used the phrase "my king") and in texts from Sippar, Ur, and Girsu, but as "Ishtar of the stars" in god lists and astronomical texts, which also applied Ishtar's epithets related to her role as a personification of Venus to this deity.[172] In some locations Ninsianna was also known as a female deity, in which case her name can be understood as "red queen of heaven."[169]

Pinikir: originally an Elamite goddess, recognised in Mesopotamia, and as a result among Hurrians and Hittites, as an equivalent of Ishtar due to similar functions. She was identified specifically as her astral aspect (Ninsianna) in god lists.[173] In a Hittite ritual she was identified by the logogram dIsTAR and Shamash, Suen and Ningal were referred to as her family; Enki and Ishtar's sukkal were invoked in it as well.[174] in Elam she was a goddess of love and sex[175] and a heavenly deity ("mistress of heaven").[176] Due to syncretism with Ishtar and Ninsianna Pinikir was referred to as both a female and male deity in Hurro-Hittite sources.[177]

sauska: her name was frequently written with the logogram dIsTAR in Hurrian and Hittite sources, while Mesopotamian texts recognised her under the name "Ishtar of Subartu."[178] Some elements peculiar to her were associated with the Assyrian hyposthasis of Ishtar, Ishtar of Nineveh, in later times.[179] Her handmaidens Ninatta and Kulitta were incorporated into the circle of deities believed to serve Ishtar in her temple in Ashur.[180][181]

Obsolete theories

Some researchers in the past attempted to connect Ishtar to the minor goddess Ashratu,[182] the Babylonian reflection of West Semitic Athirat (Asherah), associated with Amurru,[183] but as demonstrated by Steve A. Wiggins this theory was baseless, as the sole piece of evidence that they were ever conflated or even just confused with each other was the fact Ishtar and Ashratu shared an epithet[182] - however the same epithet was also applied to Marduk, Ninurta, Nergal, and Suen,[182] and no further evidence can be found in sources such as god lists.[184] There is also no evidence that Athtart (Ashtart), the Ugaritic cognate of Ishtar, was ever confused or conflated with Athirat by the Amorites.[185]

Sumerian mythology

Origin myths

The poem of Enki and the World Order (ETCSL 1.1.3) begins by describing the god Enki and his establishment of the cosmic organization of the universe.[186] Towards the end of the poem, Inanna comes to Enki and complains that he has assigned a domain and special powers to all of the other gods except for her.[187] She declares that she has been treated unfairly.[188] Enki responds by telling her that she already has a domain and that he does not need to assign her one.[189]

Original Sumerian tablet of the Courtship of Inanna and Dumuzid

The myth of "Inanna and the Huluppu Tree", found in the preamble to the epic of Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld (ETCSL 1.8.1.4),[190] centers around a young Inanna, not yet stable in her power.[191][192] It begins with a huluppu tree, which Kramer identifies as possibly a willow,[193] growing on the banks of the river Euphrates.[193][194][195] Inanna moves the tree to her garden in Uruk with the intention to carve it into a throne once it is fully grown.[193][194][195] The tree grows and matures, but the serpent "who knows no charm", the Anz;-bird, and Lilitu (Ki-Sikil-Lil-La-Ke in Sumerian),[196] seen by some as the Sumerian forerunner to the Lilith of Jewish folklore, all take up residence within the tree, causing Inanna to cry with sorrow.[193][194][195] The hero Gilgamesh, who, in this story, is portrayed as her brother, comes along and slays the serpent, causing the Anz;-bird and Lilitu to flee.[197][194][195] Gilgamesh's companions chop down the tree and carve its wood into a bed and a throne, which they give to Inanna,[198][194][195] who fashions a pikku and a mikku (probably a drum and drumsticks respectively, although the exact identifications are uncertain),[199] which she gives to Gilgamesh as a reward for his heroism.[200][194][195]

The Sumerian hymn Inanna and Utu contains an etiological myth describing how Inanna became the goddess of sex.[201] At the beginning of the hymn, Inanna knows nothing of sex,[201] so she begs her brother Utu to take her to Kur (the Sumerian underworld),[201] so that she may taste the fruit of a tree that grows there,[201] which will reveal to her all the secrets of sex.[201] Utu complies and, in Kur, Inanna tastes the fruit and becomes knowledgeable.[201] The hymn employs the same motif found in the myth of Enki and Ninhursag and in the later Biblical story of Adam and Eve.[201]

The poem Inanna Prefers the Farmer (ETCSL 4.0.8.3.3) begins with a rather playful conversation between Inanna and Utu, who incrementally reveals to her that it is time for her to marry.[12][202] She is courted by a farmer named Enkimdu and a shepherd named Dumuzid.[12] At first, Inanna prefers the farmer,[12] but Utu and Dumuzid gradually persuade her that Dumuzid is the better choice for a husband, arguing that, for every gift the farmer can give to her, the shepherd can give her something even better.[203] In the end, Inanna marries Dumuzid.[203] The shepherd and the farmer reconcile their differences, offering each other gifts.[204] Samuel Noah Kramer compares the myth to the later Biblical story of Cain and Abel because both myths center around a farmer and a shepherd competing for divine favor and, in both stories, the deity in question ultimately chooses the shepherd.[12]

Conquests and patronage

Akkadian cylinder seal from c.;2300 BCE or thereabouts depicting the deities Inanna, Utu, Enki, and Isimud[205]

Inanna and Enki (ETCSL t.1.3.1) is a lengthy poem written in Sumerian, which may date to the Third Dynasty of Ur (c. 2112 BCE – c. 2004 BCE);[206] it tells the story of how Inanna stole the sacred mes from Enki, the god of water and human culture.[207] In ancient Sumerian mythology, the mes were sacred powers or properties belonging to the gods that allowed human civilization to exist.[208] Each me embodied one specific aspect of human culture.[208] These aspects were very diverse and the mes listed in the poem include abstract concepts such as Truth, Victory, and Counsel, technologies such as writing and weaving, and also social constructs such as law, priestly offices, kingship, and prostitution. The mes were believed to grant power over all the aspects of civilization, both positive and negative.[207]

In the myth, Inanna travels from her own city of Uruk to Enki's city of Eridu, where she visits his temple, the E-Abzu.[209] Inanna is greeted by Enki's sukkal, Isimud, who offers her food and drink.[210][211] Inanna starts up a drinking competition with Enki.[207][212] Then, once Enki is thoroughly intoxicated, Inanna persuades him to give her the mes.[207][213] Inanna flees from Eridu in the Boat of Heaven, taking the mes back with her to Uruk.[214][215] Enki wakes up to discover that the mes are gone and asks Isimud what has happened to them.[214][216] Isimud replies that Enki has given all of them to Inanna.[217][218] Enki becomes infuriated and sends multiple sets of fierce monsters after Inanna to take back the mes before she reaches the city of Uruk.[219][220] Inanna's sukkal Ninshubur fends off all of the monsters that Enki sends after them.[221][220][144] Through Ninshubur's aid, Inanna successfully manages to take the mes back with her to the city of Uruk.[221][222] After Inanna escapes, Enki reconciles with her and bids her a positive farewell.[223] It is possible that this legend may represent a historic transfer of power from the city of Eridu to the city of Uruk.[18][224] It is also possible that this legend may be a symbolic representation of Inanna's maturity and her readiness to become the Queen of Heaven.[225]

The poem Inanna Takes Command of Heaven is an extremely fragmentary, but important, account of Inanna's conquest of the Eanna temple in Uruk.[18] It begins with a conversation between Inanna and her brother Utu in which Inanna laments that the Eanna temple is not within their domain and resolves to claim it as her own.[18] The text becomes increasingly fragmentary at this point in the narrative,[18] but appears to describe her difficult passage through a marshland to reach the temple while a fisherman instructs her on which route is best to take.[18] Ultimately, Inanna reaches her father An, who is shocked by her arrogance, but nevertheless concedes that she has succeeded and that the temple is now her domain.[18] The text ends with a hymn expounding Inanna's greatness.[18] This myth may represent an eclipse in the authority of the priests of An in Uruk and a transfer of power to the priests of Inanna.[18]

Inanna briefly appears at the beginning and end of the epic poem Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta (ETCSL 1.8.2.3). The epic deals with a rivalry between the cities of Uruk and Aratta. Enmerkar, the king of Uruk, wishes to adorn his city with jewels and precious metals, but cannot do so because such minerals are only found in Aratta and, since trade does not yet exist, the resources are not available to him.[226] Inanna, who is the patron goddess of both cities,[227] appears to Enmerkar at the beginning of the poem[228] and tells him that she favors Uruk over Aratta.[229] She instructs Enmerkar to send a messenger to the lord of Aratta to ask for the resources Uruk needs.[227] The majority of the epic revolves around a great contest between the two kings over Inanna's favor.[230] Inanna reappears at the end of the poem to resolve the conflict by telling Enmerkar to establish trade between his city and Aratta.[231]

Justice myths

The original Sumerian clay tablet of Inanna and Ebih, which is currently housed in the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago

Inanna and her brother Utu were regarded as the dispensers of divine justice,[123] a role which Inanna exemplifies in several of her myths.[232] Inanna and Ebih (ETCSL 1.3.2), otherwise known as Goddess of the Fearsome Divine Powers, is a 184-line poem written by the Akkadian poet Enheduanna describing Inanna's confrontation with Mount Ebih, a mountain in the Zagros mountain range.[233] The poem begins with an introductory hymn praising Inanna.[234] The goddess journeys all over the entire world, until she comes across Mount Ebih and becomes infuriated by its glorious might and natural beauty,[235] considering its very existence as an outright affront to her own authority.[236][233] She rails at Mount Ebih, shouting:

Mountain, because of your elevation, because of your height,

Because of your goodness, because of your beauty,

Because you wore a holy garment,

Because An organized(?) you,

Because you did not bring (your) nose close to the ground,

Because you did not press (your) lips in the dust.[237]

Inanna petitions to An, the Sumerian god of the heavens, to allow her to destroy Mount Ebih.[235] An warns Inanna not to attack the mountain,[235] but she ignores his warning and proceeds to attack and destroy Mount Ebih regardless.[235] In the conclusion of the myth, she explains to Mount Ebih why she attacked it.[237] In Sumerian poetry, the phrase "destroyer of Kur" is occasionally used as one of Inanna's epithets.[238]

The poem Inanna and Shukaletuda (ETCSL 1.3.3) begins with a hymn to Inanna, praising her as the planet Venus.[239] It then introduces Shukaletuda, a gardener who is terrible at his job. All of his plants die, except for one poplar tree.[239] Shukaletuda prays to the gods for guidance in his work. To his surprise, the goddess Inanna sees his one poplar tree and decides to rest under the shade of its branches.[239] Shukaletuda removes her clothes and rapes Inanna while she sleeps.[239] When the goddess wakes up and realizes she has been violated, she becomes furious and determines to bring her attacker to justice.[239] In a fit of rage, Inanna unleashes horrible plagues upon the Earth, turning water into blood.[239] Shukaletuda, terrified for his life, pleads his father for advice on how to escape Inanna's wrath.[239] His father tells him to hide in the city, amongst the hordes of people, where he will hopefully blend in.[239] Inanna searches the mountains of the East for her attacker,[239] but is not able to find him.[239] She then releases a series of storms and closes all roads to the city, but is still unable to find Shukaletuda,[239] so she asks Enki to help her find him, threatening to leave her temple in Uruk if he does not.[239] Enki consents and Inanna flies "across the sky like a rainbow".[239] Inanna finally locates Shukaletuda, who vainly attempts to invent excuses for his crime against her. Inanna rejects these excuses and kills him.[240] Theology professor Jeffrey Cooley has cited the story of Shukaletuda as a Sumerian astral myth, arguing that the movements of Inanna in the story correspond with the movements of the planet Venus.[83] He has also stated that, while Shukaletuda was praying to the goddess, he may have been looking toward Venus on the horizon.[240]

The text of the poem Inanna and Bilulu (ETCSL 1.4.4), discovered at Nippur, is badly mutilated[241] and scholars have interpreted it in a number of different ways.[241] The beginning of the poem is mostly destroyed,[241] but seems to be a lament.[241] The intelligible part of the poem describes Inanna pining after her husband Dumuzid, who is in the steppe watching his flocks.[241][242] Inanna sets out to find him.[241] After this, a large portion of the text is missing.[241] When the story resumes, Inanna is being told that Dumuzid has been murdered.[241] Inanna discovers that the old bandit woman Bilulu and her son Girgire are responsible.[243][242] She travels along the road to Edenlila and stops at an inn, where she finds the two murderers.[241] Inanna stands on top of a stool[241] and transforms Bilulu into "the waterskin that men carry in the desert",[241][244][243][242] forcing her to pour the funerary libations for Dumuzid.[241][242]

Descent into the underworld

Copy of the Akkadian version of Ishtar's Descent into the Underworld from the Library of Assurbanipal, currently held in the British Museum in London, England

Depiction of Inanna/Ishtar from the Ishtar Vase, dating to the early second millennium BCE (Mesopotamian, Terracotta with cut, moulded, and painted decoration, from Larsa)

Two different versions of the story of Inanna/Ishtar's descent into the underworld have survived:[245][246] a Sumerian version dating to the Third Dynasty of Ur (circa 2112 BCE – 2004 BCE) (ETCSL 1.4.1)[245][246] and a clearly derivative Akkadian version from the early second millennium BCE.[245][246] The Sumerian version of the story is nearly three times the length of the later Akkadian version and contains much greater detail.[247]

Sumerian version

In Sumerian religion, the Kur was conceived of as a dark, dreary cavern located deep underground;[248] life there was envisioned as "a shadowy version of life on earth".[248] It was ruled by Inanna's sister, the goddess Ereshkigal.[125][248] Before leaving, Inanna instructs her minister and servant Ninshubur to plead with the deities Enlil, Nanna, An, and Enki to rescue her if she does not return after three days.[249][250] The laws of the underworld dictate that, with the exception of appointed messengers, those who enter it may never leave.[249] Inanna dresses elaborately for the visit; she wears a turban, wig, lapis lazuli necklace, beads upon her breast, the 'pala dress' (the ladyship garment), mascara, a pectoral, and golden ring, and holds a lapis lazuli measuring rod.[251][252] Each garment is a representation of a powerful me she possesses.[253]

Inanna pounds on the gates of the underworld, demanding to be let in.[254][255][250] The gatekeeper Neti asks her why she has come[254][256] and Inanna replies that she wishes to attend the funeral rites of Gugalanna, the "husband of my elder sister Ereshkigal".[125][254][256] Neti reports this to Ereshkigal,[257][258] who tells him: "Bolt the seven gates of the underworld. Then, one by one, open each gate a crack. Let Inanna enter. As she enters, remove her royal garments."[259] Perhaps Inanna's garments, unsuitable for a funeral, along with Inanna's haughty behavior, make Ereshkigal suspicious.[260] Following Ereshkigal's instructions, Neti tells Inanna she may enter the first gate of the underworld, but she must hand over her lapis lazuli measuring rod. She asks why, and is told, "It is just the ways of the underworld." She obliges and passes through. Inanna passes through a total of seven gates, at each one removing a piece of clothing or jewelry she had been wearing at the start of her journey,[261] thus stripping her of her power.[262][250] When she arrives in front of her sister, she is naked:[262][250]

After she had crouched down and had her clothes removed, they were carried away. Then she made her sister Erec-ki-gala rise from her throne, and instead she sat on her throne. The Anna, the seven judges, rendered their decision against her. They looked at her – it was the look of death. They spoke to her – it was the speech of anger. They shouted at her – it was the shout of heavy guilt. The afflicted woman was turned into a corpse. And the corpse was hung on a hook.[263]

Three days and three nights pass, and Ninshubur, following instructions, goes to the temples of Enlil, Nanna, An, and Enki, and pleads with each of them to rescue Inanna.[264][265][266] The first three deities refuse, saying Inanna's fate is her own fault,[264][267][268] but Enki is deeply troubled and agrees to help.[269][270][268] He creates two sexless figures named gala-tura and the kur-jara from the dirt under the fingernails of two of his fingers.[269][271][268] He instructs them to appease Ereshkigal[269][271] and, when she asks them what they want, ask for the corpse of Inanna, which they must sprinkle with the food and water of life.[269][271] When they come before Ereshkigal, she is in agony like a woman giving birth.[272] She offers them whatever they want, including life-giving rivers of water and fields of grain, if they can relieve her,[273] but they refuse all of her offers and ask only for Inanna's corpse.[272] The gala-tura and the kur-jara sprinkle Inanna's corpse with the food and water of life and revive her.[274][275][268] Galla demons sent by Ereshkigal follow Inanna out of the underworld, insisting that someone else must be taken to the underworld as Inanna's replacement.[276][277][268] They first come upon Ninshubur and attempt to take her,[276][277][268] but Inanna stops them, insisting that Ninshubur is her loyal servant and that she had rightfully mourned for her while she was in the underworld.[276][277][268] They next come upon Shara, Inanna's beautician, who is still in mourning.[278][279][268] The demons attempt to take him, but Inanna insists that they may not, because he had also mourned for her.[280][281][268] The third person they come upon is Lulal, who is also in mourning.[280][282][268] The demons try to take him, but Inanna stops them once again.[280][282][268]

Ancient Sumerian cylinder seal impression showing Dumuzid being tortured in the underworld by the galla demons

Finally, they come upon Dumuzid, Inanna's husband.[283][268] Despite Inanna's fate, and in contrast to the other individuals who were properly mourning her, Dumuzid is lavishly clothed and resting beneath a tree, or upon her throne, entertained by slave-girls. Inanna, displeased, decrees that the galla shall take him.[283][268][284] The galla then drag Dumuzid down to the underworld.[283][268] Another text known as Dumuzid's Dream (ETCSL 1.4.3) describes Dumuzid's repeated attempts to evade capture by the galla demons, an effort in which he is aided by the sun-god Utu.[285][286][e]

In the Sumerian poem The Return of Dumuzid, which begins where The Dream of Dumuzid ends, Dumuzid's sister Geshtinanna laments continually for days and nights over Dumuzid's death, joined by Inanna, who has apparently experienced a change of heart, and Sirtur, Dumuzid's mother.[287] The three goddesses mourn continually until a fly reveals to Inanna the location of her husband.[288] Together, Inanna and Geshtinanna go to the place where the fly has told them they will find Dumuzid.[289] They find him there and Inanna decrees that, from that point onwards, Dumuzid will spend half of the year with her sister Ereshkigal in the underworld and the other half of the year in Heaven with her, while his sister Geshtinanna takes his place in the underworld.[290][268][291]

Akkadian version

The Akkadian version begins with Ishtar approaching the gates of the underworld and demanding the gatekeeper to let her in:

If you do not open the gate for me to come in,

I shall smash the door and shatter the bolt,

I shall smash the doorpost and overturn the doors,

I shall raise up the dead and they shall eat the living:

And the dead shall outnumber the living![292]

The gatekeeper (whose name is not given in the Akkadian version[292]) hurries to tell Ereshkigal of Ishtar's arrival. Ereshkigal orders him to let Ishtar enter, but tells him to "treat her according to the ancient rites".[293] The gatekeeper lets Ishtar into the underworld, opening one gate at a time.[293] At each gate, Ishtar is forced to shed one article of clothing. When she finally passes the seventh gate, she is naked.[294] In a rage, Ishtar throws herself at Ereshkigal, but Ereshkigal orders her servant Namtar to imprison Ishtar and unleash sixty diseases against her.[295]

After Ishtar descends to the underworld, all sexual activity ceases on earth.[296] The god Papsukkal, the Akkadian counterpart to Ninshubur,[297] reports the situation to Ea, the god of wisdom and culture.[296] Ea creates an androgynous being called Asu-shu-namir and sends them to Ereshkigal, telling them to invoke "the name of the great gods" against her and to ask for the bag containing the waters of life. Ereshkigal becomes enraged when she hears Asu-shu-namir's demand, but she is forced to give them the water of life. Asu-shu-namir sprinkles Ishtar with this water, reviving her. Then, Ishtar passes back through the seven gates, receiving one article of clothing back at each gate, and exiting the final gate fully clothed.[296]

Interpretations in modern assyriology

The "Burney Relief", which is speculated to represent either Ishtar or her older sister Ereshkigal (c. 19th or 18th century BCE)

Dina Katz, an authority on Sumerian afterlife beliefs and funerary customs, considers the narrative of Inanna's descent to be a combination of two distinct preexisting traditions rooted in broader context of Mesopotamian religion.

In one tradition, Inanna was only able to leave the underworld with the help of Enki's trick, with no mention of the possibility of finding a substitute.[298] This part of the myth belongs to the genre of myths about deities struggling to obtain power, glory etc. (such as Lugal-e or Enuma Elish),[298] and possibly served as a representation of Inanna's character as a personification of a periodically vanishing astral body.[299] According to Katz, the fact that Inanna's instructions to Ninshubur contain a correct prediction of her eventual fate, including the exact means of her rescue, show that the purpose of this composition was simply highlighting Inanna's ability to traverse both the heavens and the underworld, much like how Venus was able to rise over and over again.[299] She also points out Inanna's return has parallels in some Udug-hul incantations.[299]

Another was simply one of the many myths about the death of Dumuzi (such as Dumuzi's Dream or Inana and Bilulu; in these myths Inanna isn't to blame for his death),[300] tied to his role as an embodiment of vegetation. She considers it possible that the connection between the two parts of the narrative was meant to mirror some well attested healing rituals which required a symbolic substitute of the person being treated.[99]

Katz also notes that the Sumerian version of the myth is not concerned with matters of fertility, and points out any references to it (e.g. to nature being infertile while Ishtar is dead) were only added in later Akkadian translations;[301] so was the description of Tammuz's funeral.[301] The purpose of these changes was likely to make the myth closer to cultic traditions linked to Tammuz, namely the annual mourning of his death followed by celebration of a temporary return.[302] According to Katz it is notable that known many copies of the later versions of the myth come from Assyrian cities which were known for their veneration of Tammuz, such as Ashur and Nineveh.[301]

Other interpretations

A number of less scholarly interpretations of the myth arose through the 20th century, many of them rooted in the tradition of Jungian analysis rather than assyriology. Some authors draw comparisons to the Greek myth of the abduction of Persephone as well.[303]

Diane Wolkstein interprets the myth as a union between Inanna and her own "dark side": her twin sister-self, Ereshkigal. When Inanna ascends from the underworld, it is through Ereshkigal's powers, but, while Inanna is in the underworld, it is Ereshkigal who apparently takes on the powers of fertility. The poem ends with a line in praise, not of Inanna, but of Ereshkigal. Wolkstein interprets the narrative as a praise-poem dedicated to the more negative aspects of Inanna's domain, symbolic of an acceptance of the necessity of death in order to facilitate the continuance of life.[304] It should be pointed out that cultic texts such as god lists do not associate Ereshkigal and Inanna with each other: the former doesn't belong to the circle of Inanna's hyposthases and attendants, but to a grouping of underworld gods (Ninazu, Ningishzida, Inshushinak, Tishpak, etc.) in the famous An-Anum god list;[305] and her "alter egos" in various god lists were similar foreign deities (Hurrian queen of the dead Allani, Hattian and Hittite death deity Lelwani etc.),[306][307] not Inanna.

Joseph Campbell interpreted the myth as a tale about the psychological power of a descent into the unconscious, the realization of one's own strength through an episode of seeming powerlessness, and the acceptance of one's own negative qualities.[308]

Later myths

Epic of Gilgamesh

Ancient Mesopotamian terracotta relief showing Gilgamesh slaying the Bull of Heaven, sent by Ishtar in Tablet VI of the Epic of Gilgamesh after he spurns her amorous advances[309]

Main article: Epic of Gilgamesh

In the Akkadian Epic of Gilgamesh, Ishtar appears to Gilgamesh after he and his companion Enkidu have returned to Uruk from defeating the ogre Humbaba and demands Gilgamesh to become her consort.[310] Gilgamesh refuses her, pointing out that all of her previous lovers have suffered:[310]

Listen to me while I tell the tale of your lovers. There was Tammuz, the lover of your youth, for him you decreed wailing, year after year. You loved the many-coloured Lilac-breasted Roller, but still you struck and broke his wing [...] You have loved the lion tremendous in strength: seven pits you dug for him, and seven. You have loved the stallion magnificent in battle, and for him you decreed the whip and spur and a thong [...] You have loved the shepherd of the flock; he made meal-cake for you day after day, he killed kids for your sake. You struck and turned him into a wolf; now his own herd-boys chase him away, his own hounds worry his flanks.[96]

Infuriated by Gilgamesh's refusal,[310] Ishtar goes to heaven and tells her father Anu that Gilgamesh has insulted her.[310] Anu asks her why she is complaining to him instead of confronting Gilgamesh herself.[310] Ishtar demands that Anu give her the Bull of Heaven[310] and swears that if he does not give it to her, she will "break in the doors of hell and smash the bolts; there will be confusion [i.e., mixing] of people, those above with those from the lower depths. I shall bring up the dead to eat food like the living; and the hosts of the dead will outnumber the living."[311]

Original Akkadian Tablet XI (the "Deluge Tablet") of the Epic of Gilgamesh

Anu gives Ishtar the Bull of Heaven, and Ishtar sends it to attack Gilgamesh and his friend Enkidu.[309][312] Gilgamesh and Enkidu kill the Bull and offer its heart to the sun-god Shamash.[313][312] While Gilgamesh and Enkidu are resting, Ishtar stands up on the walls of Uruk and curses Gilgamesh.[313][314] Enkidu tears off the Bull's right thigh and throws it in Ishtar's face,[313][314] saying, "If I could lay my hands on you, it is this I should do to you, and lash your entrails to your side."[315] (Enkidu later dies for this impiety.)[314] Ishtar calls together "the crimped courtesans, prostitutes and harlots"[313] and orders them to mourn for the Bull of Heaven.[313][314] Meanwhile, Gilgamesh holds a celebration over the Bull of Heaven's defeat.[316][314]

Later in the epic, Utnapishtim tells Gilgamesh the story of the Great Flood,[317] which was sent by the god Enlil to annihilate all life on earth because the humans, who were vastly overpopulated, made too much noise and prevented him from sleeping.[318] Utnapishtim tells how, when the flood came, Ishtar wept and mourned over the destruction of humanity, alongside the Anunnaki.[319] Later, after the flood subsides, Utnapishtim makes an offering to the gods.[320] Ishtar appears to Utnapishtim wearing a lapis lazuli necklace with beads shaped like flies and tells him that Enlil never discussed the flood with any of the other gods.[321] She swears him that she will never allow Enlil to cause another flood[321] and declares her lapis lazuli necklace a sign of her oath.[321] Ishtar invites all the gods except for Enlil to gather around the offering and enjoy.[322]

Other tales

A myth about the childhood of the god Ishum, viewed as a son of Shamash, describes Ishtar seemingly temporarily taking care of him, and possibly expressing annoyance at that situation.[323]

In a pseudepigraphical Neo-Assyrian text written in the seventh century BCE, but which claims to be the autobiography of Sargon of Akkad,[324] Ishtar is claimed to have appeared to Sargon "surrounded by a cloud of doves" while he was working as a gardener for Akki, the drawer of the water.[324] Ishtar then proclaimed Sargon her lover and allowed him to become the ruler of Sumer and Akkad.[324]

In Hurro-Hittite texts the logogram dISHTAR denotes the goddess sauska, who was identified with Ishtar in god lists and similar documents as well and influenced the development of the late Assyrian cult of Ishtar of Nineveh according to hittitologist Gary Beckman.[178] She plays a prominent role in the Hurrian myths of the Kumarbi cycle.[325]

Later influence

In antiquity

Phoenician figure dating to the seventh century BCE representing a goddess, probably Astarte, called the "Lady of Galera" (National Archaeological Museum of Spain)

The cult of Inanna/Ishtar may have been introduced to the Kingdom of Judah during the reign of King Manasseh[326] and, although Inanna herself is not directly mentioned in the Bible by name,[327] the Old Testament contains numerous allusions to her cult.[328] Jeremiah 7:18 and Jeremiah 44:15–19 mention "the Queen of Heaven", who is probably a syncretism of Inanna/Ishtar and the West Semitic goddess Astarte.[326][329][330][65] Jeremiah states that the Queen of Heaven was worshipped by women who baked cakes for her.[67]

The Song of Songs bears strong similarities to the Sumerian love poems involving Inanna and Dumuzid,[331] particularly in its usage of natural symbolism to represent the lovers' physicality.[331] Song of Songs 6:10 Ezekiel 8:14 mentions Inanna's husband Dumuzid under his later East Semitic name Tammuz[332][333][334] and describes a group of women mourning Tammuz's death while sitting near the north gate of the Temple in Jerusalem.[333][334] Marina Warner (a literary critic rather than Assyriologist) claims that early Christians in the Middle East assimilated elements of Ishtar into the cult of the Virgin Mary.[335] She argues that the Syrian writers Jacob of Serugh and Romanos the Melodist both wrote laments in which the Virgin Mary describes her compassion for her son at the foot of the cross in deeply personal terms closely resembling Ishtar's laments over the death of Tammuz.[336] However, broad comparisons between Tammuz and other dying gods are rooted in the work of James George Frazer and are regarded as a relic of less rigorous early 20th century Assyriology by more recent publications.[337]

The cult of Inanna/Ishtar also heavily influenced the cult of the Phoenician goddess Astarte.[338] The Phoenicians introduced Astarte to the Greek islands of Cyprus and Cythera,[329][339] where she either gave rise to or heavily influenced the Greek goddess Aphrodite.[340][339][341][338] Aphrodite took on Inanna/Ishtar's associations with sexuality and procreation.[342][343] Furthermore, she was known as Ourania (;;;;;;;), which means "heavenly",[344][343] a title corresponding to Inanna's role as the Queen of Heaven.[344][343]

Altar from the Greek city of Taras in Magna Graecia, dating to c. 400 – c. 375 BCE, depicting Aphrodite and Adonis, whose myth is derived from the Mesopotamian myth of Inanna and Dumuzid[345][346]

Early artistic and literary portrayals of Aphrodite are extremely similar to Inanna/Ishtar.[342][343] Aphrodite was also a warrior goddess;[342][339][347] the second-century AD Greek geographer Pausanias records that, in Sparta, Aphrodite was worshipped as Aphrodite Areia, which means "warlike".[348][349] He also mentions that Aphrodite's most ancient cult statues in Sparta and on Cythera showed her bearing arms.[348][349][350][342] Modern scholars note that Aphrodite's warrior-goddess aspects appear in the oldest strata of her worship[351] and see it as an indication of her Near Eastern origins.[351][347] Aphrodite also absorbed Ishtar's association with doves,[80][347] which were sacrificed to her alone.[347] The Greek word for "dove" was perister;,[80][81] which may be derived from the Semitic phrase pera; Istar, meaning "bird of Ishtar".[81] The myth of Aphrodite and Adonis is derived from the story of Inanna and Dumuzid.[345][346]

Classical scholar Charles Penglase has written that Athena, the Greek goddess of wisdom and war, resembles Inanna's role as a "terrifying warrior goddess".[352] Others have noted that the birth of Athena from the head of her father Zeus could be derived from Inanna's descent into and return from the Underworld.[353] However, as noted by Gary Beckman, a rather direct parallel to Athena's birth is found in the Hurrian Kumarbi cycle, where Teshub is born from the surgically split skull of Kumarbi,[354] rather than in any Inanna myths.