Снег в негативе

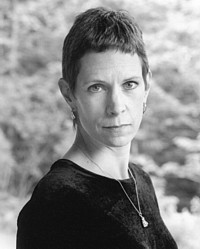

Чейз Твичелл, р. 1950

Мороз, на лужах лёд

В опавших листьев чашках.

Иду вслед за отцом, с ним горсть

Ещё мужчин и сеттер суетится

По полю и подлеском.

Моей работой было птиц носить.

Их ощипать я успевала

До возвращения к машине.

А тогда, гуляя, выискивала лужи -

Те, что пропустила,

И лёд на них крушила.

С тех пор немало

Ночей безлунных над могилой пробежало,

Как снега негатив.

Но инвалидная коляска

Всплывает в памяти порой,

И жалобы отца в гостиной,

Его проклятья Богу,

И анальгетиков никчемность,

И докторов, которые

В тот самый миг

Морфина увеличивали дозы,

В листке больничном не заметив

Одно лишь слово: «алкоголик».

А слово это означало, что больная печень

Опиаты отсылала прямо

В мозг, в его прекрасный, хрупкий мозг,

Который был ещё любить способен.

Отец тогда вовсю держался;

Он был по жизни крепок - твёрже древесины.

Так умер он впервые.

From “Dog Language”, Copper Canyon Press, 2005

Черновой перевод: 21 марта 2016 года

A Negative of Snow

Chase Twichell, b. 1950

Ice on the puddles,

in the cups of fallen leaves.

I’d walk with Dad and a handful

of other men, the setters working

the fields, the underbrush.

It was my job to carry the birds.

I’d have them all plucked

by the time we got back to the car.

On the walk out I’d look

for puddles I’d missed

and break them.

Though many moonless nights

have fallen on the grave

like a negative of snow,

Dad’s wheelchair sometimes

flashes in my mind, and I hear

the bleating down the hall,

a voice berating its god,

his worthless anodynes,

and the doctors who were

at that very moment

increasing his morphine,

having failed to note

the word alcoholic on his chart,

meaning that his damaged liver

routed the opiates straight

to his brain, his beautiful fragile brain,

which I had not yet finished loving.

My father, who still had manners,

who was a hardwood, a tough tree.

That was his first death.

Свидетельство о публикации №119061300856