Drawing with Light 24... Wed, 21 Aug 2013

DRAWING WITH LIGHT 24

= На честном слове

и на 1 крыле+

к/ф «Обнимая небо»

25.09.2014 23:32

некоторые мои стихи =это= истории в карти-

нках понятные только моим близким друзьям

-=-

…прощу прощения у случайных читателей )))))

http://lattelisa.blogspot.ru/2013/08/drawing-with-light-24.html

Drawing With Light 24 =i= Wednesday, 21 August 2013

21 августа 2013 года

Злом подстрекаемы чьим рвутся нежные узы - не знаю:

Этой великой вины взять на себя не могу.

Зло навалилось, и силы сгубило сжигающим жалом, -

Рок ли виною тому или виной божество?

Что понапрасну богов обвинять?

Сенека.

http://lib.ru/POEEAST/SENEKA/epigrammy.txt

из цикла стихов в картинках

= Неназидательные беседы с маленьким рыжим котёнком Мурзиком =

© Copyright: Backwind, 2013

Свидетельство о публикации №113082106908

((((((( вот как-то так )))))))

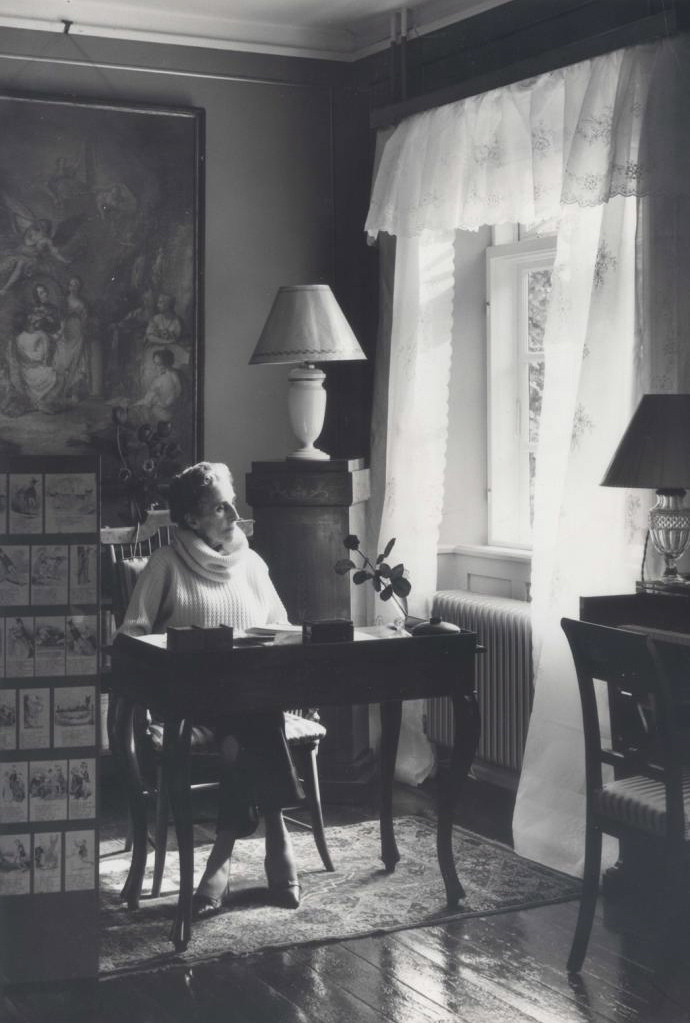

This is author Karen Blixen at her desk in Rungstedlund in Denmark, the house she grew up in and returned to when she had to give up her farm in Africa. This is the house where she wrote all her stories and lived in until the day she died, 7 September 1962. Those of you who follow my blog probably know that I have been reading Blixen's books this summer and biographies of Blixen. I'm so consumed with her that when I give A his morning kiss he usually asks me: "How is Lisa Blixen today?" I thought about posting this photo without any text but I wanted to include a story from her book Shadows on the Grass, a short, beautifully written book. The story is about the powers of a king's letter.

Blixen had received a thank-you letter from King Christian X of Denmark after sending him a lion skin as a gift.

A letter from home always means a lot to people living for a long time out of their country. They will carry it about in their pocket for several days, to take it out from time to time and read it again. A letter from a king will mean more than other letters ... I stuck the letter into the pocket of my old khaki slacks and rode out on the farm.

A moment later there was a horrible accident in the woodland on the farm. A big tree fell on one of the natives, Kitau, and badly crushed his leg. He was lying in great pain and moaning when she arrived on the scene. A runner was sent for the car so Kitau could be brought to hospital in Nairobi and while waiting Blixen sat with him. She had morphine on the farm in case of injuries but out there in the woods, miles away from the house, she had nothing to relieve his pain.

Blixen always carried bits of sugar in her pockets and gave them to boys who herded their goats and sheep on the plain. She fed Kitau with the sugars while they were waiting. As his hands were bruised after the accident, he let her place the sugar on his tongue. "It was as if this medicine did somehow relieve his pain; his moans, while he had it in his mouth, changed into low whimperings." When she ran out of sugar all she could do was watching him suffer while he kept asking for more.

In my distress I once more put my hand into my pocket and felt the King's letter ... 'I have got something more. I have got something mzuri sana' — very excellent indeed. 'I have got a Barua a Soldani' — a letter from a king. 'And that is a thing which all people know, that a letter from a king, mokone yake' — in his own hand — 'will do away with all pain, however bad.' At that I laid the King's letter on his chest and my hand upon it. I endeavoured, I believe — out there in the forest, where Kitau and I were as if all alone — to lay the whole of my strength into it.

It was a very strange thing that almost at once the words and the gesture seemed to send an effect through him. His terribly distorted face smoothed out, he closed his eyes. After a while he again looked up at me. His eyes were so much like those of a small child that cannot yet speak that I was almost surprised when he spoke to me. 'Yes,' he said. 'It is mzuri,' and again, 'yes, it is mzuri sana. Keep it there.'

When the car finally arrived he asked her to sit with him and keep on holding the letter, which she did until they arrived at the hospital. To make a long story short, Kitau's leg healed well and the accident only left him with a permanent limp.

The rumour of the powers of that king's letter soon spread on the farm and the natives brought sick people and people in pain to the farm in the hope of having the letter laid on them. Some even wanted to borrow it for a day or two to bring relief to some relative. Eventually it was decided that "it must be made use of solely in uttermost need."

- from the chapter Barua a Soldani

I don't really know why I felt the need to tell you this story. It has been about three weeks since I read the book and this story hasn't left my mind. Maybe the reason is that this king was the king of Iceland until it gained independence from Denmark in 1944. This same king infuriated Adolf Hitler back in 1942 - during the German occupation of Denmark in WWII - when he replied to Hitler's birthday greeting with a short thank you, which he signed Chr. Rex.

The powerful words of a king.

…и благодарю автора этого блога

…я даже пост от каста не отличаю

WELCOME TO LATTELISA

I'm Lisa Hjalt, an Icelander living in South Yorkshire after some country-hopping in the last years. Books are my soft spot (do I judge a book by its cover? yes, I do) and I don't say no to a cup of latte, or any other cup of quality coffee. My blog is an outlet for what inspires me on daily basis, be it interior design and styling, textiles, photography, art, travel, stationery, fashion design …

Contact by email:

lattelisablog[at]gmail.com

-=-

Морской рак и ворон (японская народная сказка)

В старину это было, в глубокую старину.

Бродил из деревни в деревню один нищий монах. Зашел он однажды по дороге в чайный домик. Ест данго (колобок) и чай попивает.

Поел он, попил, а потом говорит:

— Хозяйка, хочешь, я тебе нарисую картину? «Какую картину может нарисовать этот оборвыш?» — подумала хозяйка.

А монах снял с одной ноги соломенную сандалию, обмакнул её в тушь и сказал:

— Пожалуй, так занятней рисовать, чем кистью! — и начертил на фусума (двери) большого ворона.

Пошёл дальше нищий монах. Стоит на склоне горы другой чайный домик. Отдохнул там монах, выпил чаю и говорит:

— Хозяйка, хочешь, я тебе что-нибудь нарисую? Снял он сандалию с другой ноги, обмакнул в чёрную тушь и нарисовал на фусума морского рака.

Рак был совсем как живой: он шевелил хвостом и клешнями.

Множество людей приходило в чайный домик полюбоваться на морского рака. Деньги так и посыпались в кошель к хозяйке.

Прошло время. На обратном пути завернул нищий монах в тот чайный домик, где нарисовал он морского рака.

Стала хозяйка благодарить монаха:

— Вот спасибо вам! Прекрасного рака вы нарисовали. Только больно чёрен. Сделайте его, пожалуйста, ярко-красным!

— Что же, это дело простое! — ответил монах и выкрасил рака в красный цвет.

«Вот хорошо-то,— с торжеством подумала хозяйка,— теперь я ещё больше денег заработаю».

Но красный рак был мёртвый. Не шевелил он больше ни хвостом, ни клешнями. И никто уже не приходил на него любоваться.

А нищий монах завернул по пути в тот чайный домик, где он ворона нарисовал.

Хозяйка дома встретила его неласково, начала жаловаться:

— Заляпал своим вороном мои чистые фусума, вконец испортил! Сотри свою картину, да и только!

— Это дело простое,— улыбнулся монах.— Тебе не нравится этот ворон? Сейчас его не будет!

Достал он из-за пазухи веер, раскрыл его и несколько раз взмахнул им в воздухе...

И вдруг послышалось: «Кра-кра-кра!» Ворон ожил, расправил крылья и улетел.

Онемела хозяйка от удивления, а нищий монах пошёл дальше своим путём.

Сказки Японии / Пер. с яп. В. Марковой; Сост. Т. Редько-

Добровольская. - М.: ТЕРРА - Книжный клуб, 2002, стр. 11.

…и маленький рождественский подарок для тех, кто читает по-английски

THE GIFT OF THE MAGI

(The Four Million, by O. Henry)

One dollar and eighty-seven cents. That was all. And sixty cents of it was in pennies. Pennies saved one and two at a time by bulldozing the grocer and the vegetable man and the butcher until one's cheeks burned with the silent imputation of parsimony that such close dealing implied. Three times Della counted it. One dollar and eighty-seven cents. And the next day would be Christmas.

There was clearly nothing to do but flop down on the shabby little couch and howl. So Della did it. Which instigates the moral reflection that life is made up of sobs, sniffles, and smiles, with sniffles predominating.

While the mistress of the home is gradually subsiding from the first stage to the second, take a look at the home. A furnished flat at $8 per week. It did not exactly beggar description, but it certainly had that word on the lookout for the mendicancy squad.

In the vestibule below was a letter-box into which no letter would go, and an electric button from which no mortal finger could coax a ring. Also appertaining thereunto was a card bearing the name "Mr. James Dillingham Young." The "Dillingham" had been flung to the breeze during a former period of prosperity when its possessor was being paid $30 per week. Now, when the income was shrunk to $20, the letters of "Dillingham" looked blurred, as though they were thinking seriously of contracting to a modest and unassuming D. But whenever Mr. James Dillingham Young came home and reached his flat above he was called "Jim" and greatly hugged by Mrs. James Dillingham Young, already introduced to you as Della. Which is all very good.

Della finished her cry and attended to her cheeks with the powder rag. She stood by the window and looked out dully at a grey cat walking a grey fence in a grey backyard. Tomorrow would be Christmas Day, and she had only $1.87 with which to buy Jim a present. She had been saving every penny she could for months, with this result. Twenty dollars a week doesn't go far. Expenses had been greater than she had calculated. They always are. Only $1.87 to buy a present for Jim. Her Jim. Many a happy hour she had spent planning for something nice for him. Something fine and rare and sterling—something just a little bit near to being worthy of the honour of being owned by Jim.

There was a pier-glass between the windows of the room. Perhaps you have seen a pier-glass in an $8 flat. A very thin and very agile person may, by observing his reflection in a rapid sequence of longitudinal strips, obtain a fairly accurate conception of his looks. Della, being slender, had mastered the art.

Suddenly she whirled from the window and stood before the glass. Her eyes were shining brilliantly, but her face had lost its colour within twenty seconds. Rapidly she pulled down her hair and let it fall to its full length.

Now, there were two possessions of the James Dillingham Youngs in which they both took a mighty pride. One was Jim's gold watch that had been his father's and his grandfather's. The other was Della's hair. Had the Queen of Sheba lived in the flat across the airshaft, Della would have let her hair hang out the window some day to dry just to depreciate Her Majesty's jewels and gifts. Had King Solomon been the janitor, with all his treasures piled up in the basement, Jim would have pulled out his watch every time he passed, just to see him pluck at his beard from envy.

So now Della's beautiful hair fell about her, rippling and shining like a cascade of brown waters. It reached below her knee and made itself almost a garment for her. And then she did it up again nervously and quickly. Once she faltered for a minute and stood still while a tear or two splashed on the worn red carpet.

On went her old brown jacket; on went her old brown hat. With a whirl of skirts and with the brilliant sparkle still in her eyes, she fluttered out the door and down the stairs to the street.

Where she stopped the sign read: "Mme. Sofronie. Hair Goods of All Kinds." One flight up Della ran, and collected herself, panting. Madame, large, too white, chilly, hardly looked the "Sofronie."

"Will you buy my hair?" asked Della.

"I buy hair," said Madame. "Take yer hat off and let's have a sight at the looks of it."

Down rippled the brown cascade. "Twenty dollars," said Madame, lifting the mass with a practised hand.

"Give it to me quick," said Della.

Oh, and the next two hours tripped by on rosy wings. Forget the hashed metaphor. She was ransacking the stores for Jim's present.

She found it at last. It surely had been made for Jim and no one else. There was no other like it in any of the stores, and she had turned all of them inside out. It was a platinum fob chain simple and chaste in design, properly proclaiming its value by substance alone and not by meretricious ornamentation—as all good things should do. It was even worthy of The Watch. As soon as she saw it she knew that it must be Jim's. It was like him. Quietness and value—the description applied to both. Twenty-one dollars they took from her for it, and she hurried home with the 87 cents. With that chain on his watch Jim might be properly anxious about the time in any company. Grand as the watch was, he sometimes looked at it on the sly on account of the old leather strap that he used in place of a chain.

When Della reached home her intoxication gave way a little to prudence and reason. She got out her curling irons and lighted the gas and went to work repairing the ravages made by generosity added to love. Which is always a tremendous task, dear friends—a mammoth task.

Within forty minutes her head was covered with tiny, close-lying curls that made her look wonderfully like a truant schoolboy. She looked at her reflection in the mirror long, carefully, and critically.

"If Jim doesn't kill me," she said to herself, "before he takes a second look at me, he'll say I look like a Coney Island chorus girl. But what could I do—oh! what could I do with a dollar and eighty-seven cents?"

At 7 o'clock the coffee was made and the frying-pan was on the back of the stove hot and ready to cook the chops.

Jim was never late. Della doubled the fob chain in her hand and sat on the corner of the table near the door that he always entered. Then she heard his step on the stair away down on the first flight, and she turned white for just a moment. She had a habit for saying little silent prayers about the simplest everyday things, and now she whispered: "Please God, make him think I am still pretty."

The door opened and Jim stepped in and closed it. He looked thin and very serious. Poor fellow, he was only twenty-two—and to be burdened with a family! He needed a new overcoat and he was without gloves.

Jim stopped inside the door, as immovable as a setter at the scent of quail. His eyes were fixed upon Della, and there was an expression in them that she could not read, and it terrified her. It was not anger, nor surprise, nor disapproval, nor horror, nor any of the sentiments that she had been prepared for. He simply stared at her fixedly with that peculiar expression on his face.

Della wriggled off the table and went for him.

"Jim, darling," she cried, "don't look at me that way. I had my hair cut off and sold because I couldn't have lived through Christmas without giving you a present. It'll grow out again—you won't mind, will you? I just had to do it. My hair grows awfully fast. Say 'Merry Christmas!' Jim, and let's be happy. You don't know what a nice—what a beautiful, nice gift I've got for you."

"You've cut off your hair?" asked Jim, laboriously, as if he had not arrived at that patent fact yet even after the hardest mental labor.

"Cut it off and sold it," said Della. "Don't you like me just as well, anyhow? I'm me without my hair, ain't I?"

Jim looked about the room curiously.

"You say your hair is gone?" he said, with an air almost of idiocy.

"You needn't look for it," said Della. "It's sold, I tell you—sold and gone, too. It's Christmas Eve, boy. Be good to me, for it went for you. Maybe the hairs of my head were numbered," she went on with sudden serious sweetness, "but nobody could ever count my love for you. Shall I put the chops on, Jim?"

Out of his trance Jim seemed quickly to wake. He enfolded his Della. For ten seconds let us regard with discreet scrutiny some inconsequential object in the other direction. Eight dollars a week or a million a year—what is the difference? A mathematician or a wit would give you the wrong answer. The magi brought valuable gifts, but that was not among them. This dark assertion will be illuminated later on.

Jim drew a package from his overcoat pocket and threw it upon the table.

"Don't make any mistake, Dell," he said, "about me. I don't think there's anything in the way of a haircut or a shave or a shampoo that could make me like my girl any less. But if you'll unwrap that package you may see why you had me going a while at first."

White fingers and nimble tore at the string and paper. And then an ecstatic scream of joy; and then, alas! a quick feminine change to hysterical tears and wails, necessitating the immediate employment of all the comforting powers of the lord of the flat.

For there lay The Combs—the set of combs, side and back, that Della had worshipped long in a Broadway window. Beautiful combs, pure tortoise shell, with jewelled rims—just the shade to wear in the beautiful vanished hair. They were expensive combs, she knew, and her heart had simply craved and yearned over them without the least hope of possession. And now, they were hers, but the tresses that should have adorned the coveted adornments were gone.

But she hugged them to her bosom, and at length she was able to look up with dim eyes and a smile and say: "My hair grows so fast, Jim!"

And then Della leaped up like a little singed cat and cried, "Oh, oh!"

Jim had not yet seen his beautiful present. She held it out to him eagerly upon her open palm. The dull precious metal seemed to flash with a reflection of her bright and ardent spirit.

"Isn't it a dandy, Jim? I hunted all over town to find it. You'll have to look at the time a hundred times a day now. Give me your watch. I want to see how it looks on it."

Instead of obeying, Jim tumbled down on the couch and put his hands under the back of his head and smiled.

"Dell," said he, "let's put our Christmas presents away and keep 'em a while. They're too nice to use just at present. I sold the watch to get the money to buy your combs. And now suppose you put the chops on."

The magi, as you know, were wise men—wonderfully wise men—who brought gifts to the Babe in the manger. They invented the art of giving Christmas presents. Being wise, their gifts were no doubt wise ones, possibly bearing the privilege of exchange in case of duplication. And here I have lamely related to you the uneventful chronicle of two foolish children in a flat who most unwisely sacrificed for each other the greatest treasures of their house. But in a last word to the wise of these days let it be said that of all who give gifts these two were the wisest. Of all who give and receive gifts, such as they are wisest. Everywhere they are wisest. They are the magi.

и для тех, кто не читает по-английски…

О'Генри. ДАРЫ ВОЛХВОВ

© Перевод, Е.Калашникова

Один доллар восемьдесят семь центов. Это было все. Из них шестьдесят центов монетками по одному центу. За каждую из этих монеток пришлось торговаться с бакалейщиком, зеленщиком, мясником так, что даже уши горели от безмолвного неодобрения, которое вызывала подобная бережливость. Делла пересчитала три раза. Один доллар восемьдесят семь центов. А завтра Рождество.

Единственное, что тут можно было сделать, это хлопнуться на старенькую кушетку и зареветь. Именно так Делла и поступила. Откуда напрашивается философский вывод, что жизнь состоит из слез, вздохов и улыбок, причем вздохи преобладают.

Пока хозяйка дома проходит все эти стадии, оглядим самый дом. Меблированная квартирка за восемь долларов в неделю. В обстановке не то чтобы вопиющая нищета, но скорее красноречиво молчащая бедность. Внизу, на парадной двери, ящик для писем, в щель которого не протиснулось бы ни одно письмо, и кнопка электрического звонка, из которой ни одному смертному не удалось бы выдавить ни звука. К сему присовокуплялась карточка с надписью: «М-р Джеймс Диллингем Юнг». «Диллингем» развернулось во всю длину в недавний период благосостояния, когда обладатель указанного имени получал тридцать долларов в неделю. Теперь, после того, как этот доход понизился до двадцати долларов, буквы в слове «Диллингем» потускнели, словно не на шутку задумавшись: а не сократиться ли им в скромное и непритязательное «Д»? Но когда мистер Джеймс Диллингем Юнг приходил домой и поднимался к себе на верхний этаж, его неизменно встречал возглас: «Джим!» — и нежные объятия миссис Джеймс Диллингем Юнг, уже представленной вам под именем Деллы. А это, право же, очень мило.

Делла кончила плакать и прошлась пуховкой по щекам. Она теперь стояла у окна и уныло глядела на серую кошку, прогуливавшуюся по серому забору вдоль серого двора. Завтра Рождество, а у нее только один доллар восемьдесят семь центов на подарок Джиму! Долгие месяцы она выгадывала буквально каждый цент, и вот все, чего она достигла. На двадцать долларов в неделю далеко не уедешь. Расходы оказались больше, чем она рассчитывала. С расходами всегда так бывает. Только доллар восемьдесят семь центов на подарок Джиму! Ее Джиму! Сколько радостных часов она провела, придумывая, что бы такое ему подарить к Рождеству. Что-нибудь совсем особенное, редкостное, драгоценное, что-нибудь, хоть чуть-чуть достойное высокой чести принадлежать Джиму.

В простенке между окнами стояло трюмо. Вам никогда не приходилось смотреться в трюмо восьмидолларовой меблированной квартиры? Очень худой и очень подвижный человек может, наблюдая последовательную смену отражений в его узких створках, составить себе довольно точное представление о собственной внешности. Делле, которая была хрупкого сложения, удалось овладеть этим искусством.

Она вдруг отскочила от окна и бросилась к зеркалу. Глаза ее сверкали, но с лица за двадцать секунд сбежали краски. Быстрым движением она вытащила шпильки и распустила волосы.

Надо вам сказать, что у четы Джеймс Диллингем Юнг было два сокровища, составлявших предмет их гордости. Одно — золотые часы Джима, принадлежавшие его отцу и деду, другое — волосы Деллы. Если бы царица Савская проживала в доме напротив, Делла, помыв голову, непременно просушивала бы у окна распущенные волосы — специально для того, чтобы заставить померкнуть все наряды и украшения ее величества. Если бы царь Соломон служил в том же доме швейцаром и хранил в подвале все свои богатства, Джим, проходя мимо, всякий раз доставал бы часы из кармана — специально для того, чтобы увидеть, как он рвет на себе бороду от зависти.

И вот прекрасные волосы Деллы рассыпались, блестя и переливаясь, точно струи каштанового водопада. Они спускались ниже колен и плащом окутывали почти всю ее фигуру. Но она тотчас же, нервничая и торопясь, принялась снова подбирать их. Потом, словно заколебавшись, с минуту стояла неподвижно, и две или три слезинки упали на ветхий красный ковер.

Старенький коричневый жакет на плечи, старенькую коричневую шляпку на голову — и, взметнув юбками, сверкнув невысохшими блестками в глазах, она уже мчалась вниз, на улицу.

Вывеска, у которой она остановилась, гласила: «M-me Sophronie. Всевозможные изделия из волос». Делла взбежала на второй этаж и остановилась, с трудом переводя дух.

— Не купите ли вы мои волосы? — спросила она у мадам.

— Я покупаю волосы, — ответила мадам. — Снимите шляпку, надо посмотреть товар.

Снова заструился каштановый водопад.

— Двадцать долларов, — сказала мадам, привычно взвешивая на руке густую массу.

— Давайте скорее, — сказала Делла.

Следующие два часа пролетели на розовых крыльях — прошу прощенья за избитую метафору. Делла рыскала по магазинам в поисках подарка для Джима.

Наконец она нашла. Без сомнения, это было создано для Джима, и только для него. Ничего подобного не нашлось в других магазинах, а уж она все в них перевернула вверх дном. Это была платиновая цепочка для карманных часов, простого и строгого рисунка, пленявшая истинными своими качествами, а не показным блеском, — такими и должны быть все хорошие вещи. Ее, пожалуй, даже можно было признать достойной часов. Как только Делла увидела ее, она поняла, что цепочка должна принадлежать Джиму. Она была такая же, как сам Джим. Скромность и достоинство — эти качества отличали обоих. Двадцать один доллар пришлось уплатить в кассу, и Делла поспешила домой с восемьюдесятью семью центами в кармане. При такой цепочке Джиму в любом обществе не зазорно будет поинтересоваться, который час. Как ни великолепны были его часы, а смотрел он на них часто украдкой, потому что они висели на дрянном кожаном ремешке.

Дома оживление Деллы поулеглось и уступило место предусмотрительности и расчету. Она достала щипцы для завивки, зажгла газ и принялась исправлять разрушения, причиненные великодушием в сочетании с любовью. А это всегда тягчайший труд, друзья мои, исполинский труд.

Не прошло и сорока минут, как ее голова покрылась крутыми мелкими локончиками, которые сделали ее удивительно похожей на мальчишку, удравшего с уроков. Она посмотрела на себя в зеркало долгим, внимательным и критическим взглядом.

«Ну, — сказала она себе, — если Джим не убьет меня сразу, как только взглянет, он решит, что я похожа на хористку с Кони-Айленда. Но что же мне было делать, ах, что же мне было делать, раз у меня был только доллар и восемьдесят семь центов!»

В семь часов кофе был сварен, и раскаленная сковорода стояла на газовой плите, дожидаясь бараньих котлеток.

Джим никогда не запаздывал. Делла зажала платиновую цепочку в руке и уселась на краешек стола поближе к входной двери. Вскоре она услышала его шаги внизу на лестнице и на мгновение побледнела. У нее была привычка обращаться к богу с коротенькими молитвами по поводу всяких житейских мелочей, и она торопливо зашептала:

— Господи, сделай так, чтобы я ему не разонравилась!

Дверь отворилась, Джим вошел и закрыл ее за собой. У него было худое, озабоченное лицо. Нелегкое дело в двадцать два года быть обремененным семьей! Ему уже давно нужно было новое пальто, и руки мерзли без перчаток.

Джим неподвижно замер у дверей, точно сеттер, учуявший перепела. Его глаза остановились на Делле с выражением, которого она не могла понять, и ей стало страшно. Это не был ни гнев, ни удивление, ни упрек, ни ужас — ни одного из тех чувств, которых можно было бы ожидать. Он просто смотрел на нее, не отрывая взгляда, и лицо его не меняло своего странного выражения.

Делла соскочила со стола и бросилась к нему.

— Джим, милый, — закричала она, — не смотри на меня так! Я остригла волосы и продала их, потому что я не пережила бы, если б мне нечего было подарить тебе к Рождеству. Они опять отрастут. Ты ведь не сердишься, правда? Я не могла иначе. У меня очень быстро растут волосы. Ну, поздравь меня с Рождеством, Джим, и давай радоваться празднику. Если б ты знал, какой я тебе подарок приготовила, какой замечательный, чудесный подарок!

— Ты остригла волосы? — спросил Джим с напряжением, как будто, несмотря на усиленную работу мозга, он все еще не мог осознать этот факт.

— Да, остригла и продала, — сказала Делла. — Но ведь ты меня все равно будешь любить? Я ведь все та же, хоть и с короткими волосами.

Джим недоуменно оглядел комнату.

— Так, значит, твоих кос уже нет? — спросил он с бессмысленной настойчивостью.

— Не ищи, ты их не найдешь, — сказала Делла. — Я же тебе говорю: я их продала — остригла и продала. Сегодня сочельник, Джим. Будь со мной поласковее, потому что я это сделала для тебя. Может быть, волосы на моей голове и можно пересчитать, — продолжала она, и ее нежный голос вдруг зазвучал серьезно, — но никто, никто не мог бы измерить мою любовь к тебе! Жарить котлеты, Джим?

И Джим вышел из оцепенения. Он заключил свою Деллу в объятия. Будем скромны и на несколько секунд займемся рассмотрением какого-нибудь постороннего предмета. Что больше — восемь долларов в неделю или миллион в год? Математик или мудрец дадут вам неправильный ответ. Волхвы принесли драгоценные дары, но среди них не было одного. Впрочем, эти туманные намеки будут разъяснены далее.

Джим достал из кармана пальто сверток и бросил его на стол.

— Не пойми меня ложно, Делл, — сказал он. — Никакая прическа и стрижка не могут заставить меня разлюбить мою девочку. Но разверни этот сверток, и тогда ты поймешь, почему я в первую минуту немножко оторопел.

Белые проворные пальчики рванули бечевку и бумагу. Последовал крик восторга, тотчас же — увы! — чисто по-женски сменившийся потоком слез и стонов, так что потребовалось немедленно применить все успокоительные средства, имевшиеся в распоряжении хозяина дома.

Ибо на столе лежали гребни, тот самый набор гребней — один задний и два боковых, — которым Делла давно уже благоговейно любовалась в одной витрине Бродвея. Чудесные гребни, настоящие черепаховые, с вделанными в края блестящими камешками, и как раз под цвет ее каштановых волос. Они стоили дорого — Делла знала это, — и сердце ее долго изнывало и томилось от несбыточного желания обладать ими. И вот теперь они принадлежали ей, но нет уже прекрасных кос, которые украсил бы их вожделенный блеск.

Все же она прижала гребни к груди и, когда, наконец, нашла в себе силы поднять голову и улыбнуться сквозь слезы, сказала:

— У меня очень быстро растут волосы, Джим!

Тут она вдруг подскочила, как ошпаренный котенок, и воскликнула:

— Ах, боже мой!

Ведь Джим еще не видел ее замечательного подарка. Она поспешно протянула ему цепочку на раскрытой ладони. Матовый драгоценный металл, казалось, заиграл в лучах ее бурной и искренней радости.

— Разве не прелесть, Джим? Я весь город обегала, покуда нашла это. Теперь можешь хоть сто раз в день смотреть, который час. Дай-ка мне часы. Я хочу посмотреть, как это будет выглядеть все вместе.

Но Джим, вместо того чтобы послушаться, лег на кушетку, подложил обе руки под голову и улыбнулся.

— Делл, — сказал он, — придется нам пока спрятать наши подарки, пусть полежат немножко. Они для нас сейчас слишком хороши. Часы я продал, чтобы купить тебе гребни. А теперь, пожалуй, самое время жарить котлеты.

Волхвы, те, что принесли дары младенцу в яслях, были, как известно, мудрые, удивительно мудрые люди. Они-то и завели моду делать рождественские подарки. И так как они были мудры, то и дары их были мудры, может быть, даже с оговоренным правом обмена в случае непригодности. А я тут рассказал вам ничем не примечательную историю про двух глупых детей из восьмидолларовой квартирки, которые самым немудрым образом пожертвовали друг для друга своими величайшими сокровищами. Но да будет сказано в назидание мудрецам наших дней, что из всех дарителей эти двое были мудрейшими. Из всех, кто подносит и принимает дары, истинно мудры лишь подобные им. Везде и всюду. Они и есть волхвы.

Свидетельство о публикации №113082106908