Dccclxxvi - де - мон - алко - голь

Аквариус в украине

http://stihi.ru/2024/04/23/4380

+*+iiiiV @ oH0:VTi:MMM * i o V Xi o i i V o i i V i i Ч i i o o i V i X i i i V Ч i i i i ф = +#+8$€;; i i V o B

DCCXi

http://stihi.ru/2009/04/12/3632

Боже я больше так не могу

Сергей Полищук

Боже я больше так не могу

(Sergei Polischouk 01/31/2007)

Боже, я больше так не могу

Боже, я больше так не могу

Боже, Ты же видишь, что творится во мне

Я больше так не могу

Вокруг меня изнурённых сердца

Не почитали мы мать и отца

Я стою пред Тобой, не поднимая лица

Боже, я больше так не могу

Боже, открой им глаза

Боже, я не могу всё сказать

Я просто склонюсь, из глаз польётся слеза

Я не могу всё сказать

Боже, ты только можешь лечить

Только ты можешь нас научить

Научи нас друг, друга любить

Боже, открой нам глаза

Боже, на нас наброшена сеть

Мы не можем руки поднять и петь

Боже, как бы хотел я успеть

Пока мне не оборванна нить

Боже, а ведь мы все на краю

Перед нами обрыв, в пропасти бездну смотрю

Верю, ты слышишь молитву мою

Боже, на нас наброшена сеть

Боже, а ведь так просто простить

Брата вину, и все долги отпустить

Ведь нам всем из одной чаши пить

И хлеб единный вкушать

Господи, мы твоя кровь, плоть и печать

Но в наших душах еле тлеет свеча

Обиды и боль слышнее в наших речах

Боже, а ведь так просто прощать.

© Copyright: Сергей Полищук, 2009

Свидетельство о публикации №109041203632

http://stihi.ru/2009/06/14/1521

Скорбец

Сергей Полищук

Скорбец

Слова: Борис Гребенщиков

Музыка: Аквариум

Альбом: Беспечный Русский Бродяга

Для перевода или подражания

Проснулся в церкви ангельских крыл

Высоко над землей, где я так долго жил.

Небесные созданья несли мою постель -

Ворон, птица Сирин и коростель.

Земля лежала, как невеста, с которой спьяну сняли венец:

Прекрасна и чиста, но в глазах особый скорбец.

На льду Бел-озера один на один

Сошлись наш ангел Алкоголь и их демон Кокаин;

Из Китеж-града шел на выручку клир,

Внесли святой червонец - и опять вышел мир.

Мадонну Джеки Браун взял в жены наш Бог-Отец,

Вначале было плохо, но потом пришел обычный скорбец.

Я спрашивал у матери, я мучил отца

Вопросом - Как мне уйти от моего скорбеца?

Потом меня прижал в углу херувим:

"Без скорбеца ты здесь не будешь своим".

С тех пор я стал цыганом, сам себе пастух и сам дверь -

И я молюсь, как могу, чтобы мир сошел им в души теперь.

© Copyright: Сергей Полищук, 2009

Свидетельство о публикации №109061401521

http://stihi.ru/2009/06/14/1356

Мается

Сергей Полищук

Мается

Слова: Борис Гребенщиков

Музыка: Аквариум

Альбом: Навигатор

Для перевода или подражания

Мается, мается - жизнь не получается,

Хоть с вином на люди, хоть один вдвоем;

Мается, мается - то грешит, то кается;

А все не признается, что все дело в нем.

Мается, мается - то грешит, то кается;

То ли пыль во поле, то ли отчий дом;

Мается, мается - то заснет, то лается,

А все не признается, что все дело в нем.

Вроде бы и строишь - а все разлетается;

Вроде говоришь, да все не про то.

Ежели не выпьешь, то не получается,

А выпьешь - воешь волком, ни за что, ни про что...

Мается, мается - то заснет, то лается;

Хоть с вином на люди, хоть один вдвоем.

Мается, мается - Бог знает, где шляется,

А все не признается, что все дело в нем.

Может, голова моя не туда вставлена;

Может, слишком много врал, и груза не снесть.

Я бы и дышал, да грудь моя сдавлена;

Я бы вышел вон, но только там страшней, чем здесь...

Мается, мается - тропка все сужается;

Хоть с вином на люди, хоть один вдвоем.

Мается, мается; глянь, вот-вот сломается;

Чтоб ему признаться, что дело только в нем...

В белом кошелечечке - медные деньги,

В золотой купели - темнота да тюрьма;

Небо на цепи, да в ней порваны звенья;

Как пойдешь чинить - ты все поймешь сама.

© Copyright: Сергей Полищук, 2009

Свидетельство о публикации №109061401356

…

Мама, Я Не Могу Больше Пить

Слова: Борис Гребенщиков

Музыка: Аквариум

Альбом: Беспечный Русский Бродяга

Для перевода или подражания

«Демон Алкоголь - (На льду Бел-озера один на один

сошлись наш ангел алкоголь и их демон кокаин...

"Песня "Скорбец", 1998. - БГ+ после обсуждения с Толстой Татьяной Никитичной как перевести на русский язык слово - Blues»

…

Мама, я не могу больше пить.

Мама, я не могу больше пить

Мама, вылей все, что стоит на столе -

Я не могу больше пить

На мне железный аркан

Я крещусь, когда я вижу стакан

Я не в силах поддерживать этот обман

Мама, я не могу больше пить

Патриоты скажут, что я дал слабину

Практически продал родную страну

Им легко, а я иду ко дну

Я гляжу, как истончается нить

Я не валял дурака

Тридцать пять лет от звонка до звонка

Но мне не вытравить из себя чужака

Мама, я не могу больше пить

Мама, я не могу больше пить

Мама, я не могу больше пить

Мама, позвони всем моим друзьям

Скажи им - я не могу больше пить

Вот она - пропасть во ржи

Под босыми ногами ножи

Как достало жить не по лжи -

Мама, я не могу больше пить

Скажи моим братьям, что теперь я большой

Скажи сестре, что я болен душой

Я мог бы быть обычным человеком

Но я упустил эту роль

Зашел в бесконечный лес

Гляжу вверх, но я не вижу небес

Скажи в церкви, что во всех дверях стоит бес -

Демон Алкоголь

Мама, я не могу больше пить

Мама, я не могу больше пить

Мама, вылей все, что стоит на столе -

Я не могу больше пить

На мне железный аркан

Я крещусь когда я вижу стакан

Я не в силах поддерживать этот обман

Мама, я не могу больше пить

…

Mama, I Can't Drink Anymore

Lyrics: Boris Grebenshchikov

Music: Aquarium

Album: Careless Russian Vagabond

For translation or imitation

"Demon Alcohol - (On the ice of Bel-lake, one on one.

met our angel alcohol and their demon cocaine....

"The song "Scorbetz", 1998. - BG+ after discussing with Tolstaya Tatiana Nikitichnaya how to translate the word - Blues - into Russian."

...

Mama, I can't drink anymore.

Mommy, I can't drink anymore

Mommy, pour out everything on the table -

I can't drink anymore

I'm wearing an iron harness

I'm baptized when I see the glass.

I can't keep up this deception

Mom, I can't drink anymore

The patriots will say I'm weak.

I practically sold out my country.

It's easy for them, but I'm going down

; I'm watching the thread thinning ;

I didn't fool around

Thirty-five years from bell to bell

But I can't get the stranger out of me.

Mama, I can't drink anymore

Mama, I can't drink anymore

Mama, I can't drink anymore

Mama, call all my friends

; Tell them I can't drink anymore ;

There it is, the chasm in the rye

There's knives under my bare feet

I'm sick of living a lie

Mom, I can't drink anymore

Tell my brothers I'm big now

Tell my sister I'm sick at heart

I could have been a normal person

But I missed that part

I'm in an endless forest

I look up, but I can't see the sky.

Tell the church there's a demon in all the doors.

Demon Alcohol.

Mommy, I can't drink anymore

Mama, I can't drink anymore

; Mama, pour out everything on the table ;

; I can't drink no more ;

; I'm wearing an iron harness ;

I'm baptized when I see the glass

I can't keep up this deception

Mama, I can't drink anymore

...

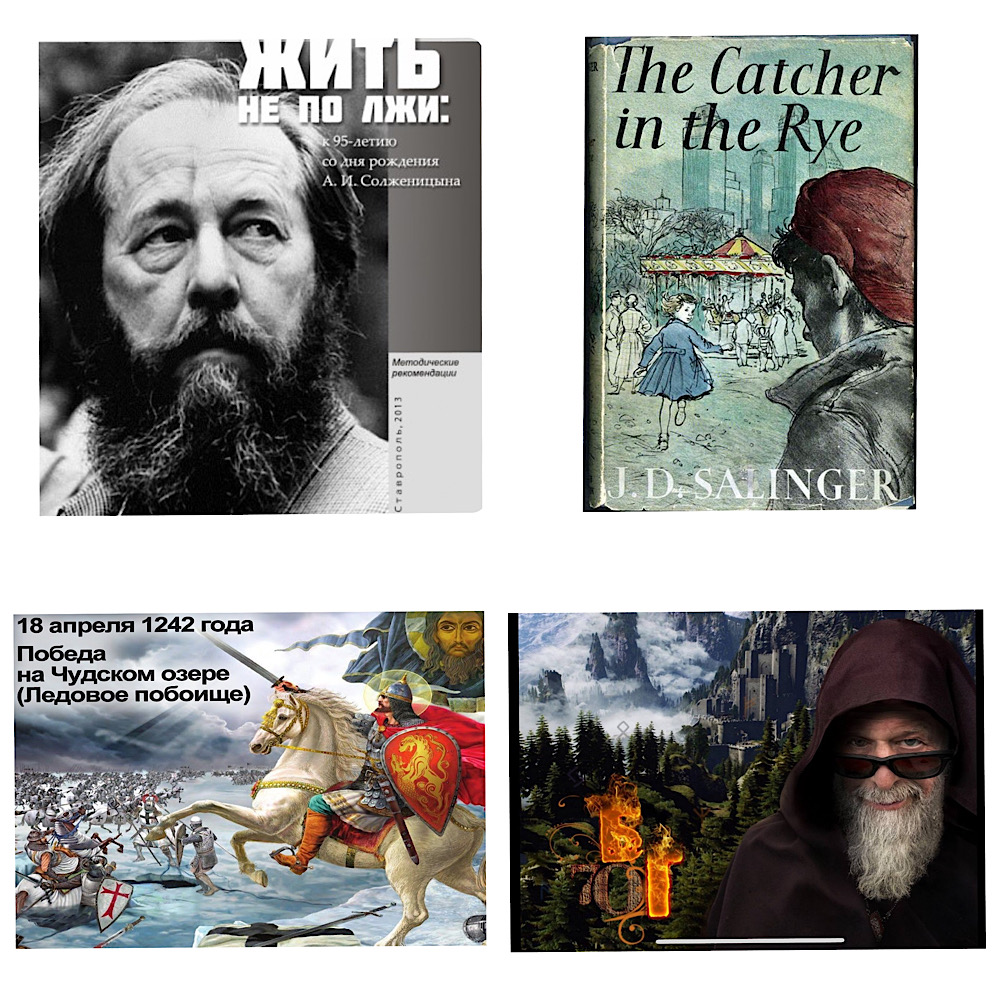

The Catcher in the Rye

1951 novel by J. D. Salinger

For other uses, see The Catcher in the Rye (disambiguation).

The Catcher in the Rye is a novel by American author J. D. Salinger that was partially published in serial form in 1945–46 before being novelized in 1951. Originally intended for adults, it is often read by adolescents for its themes of angst and alienation, and as a critique of superficiality in society. The novel also deals with themes of innocence, identity, belonging, loss, connection, sex, and depression. The main character, Holden Caulfield, has become an icon for teenage rebellion. Caulfield, nearly of age, gives his opinion on a wide variety of topics as he narrates his recent life events.

Quick Facts Author, Cover artist ...

The Catcher in the Rye has been translated widely. About one million copies are sold each year, with total sales of more than 65 million books. The novel was included on Time's 2005 list of the 100 best English-language novels written since 1923, and it was named by Modern Library and its readers as one of the 100 best English-language novels of the 20th century. In 2003, it was listed at number 15 on the BBC's survey "The Big Read".

Plot

Holden Caulfield recalls the events of a long weekend, shortly before the previous year's Christmas. The story begins at Pencey Preparatory Academy, a boarding school in Pennsylvania, where he has been expelled after failing all his classes, except English.

Later, Holden agrees to write an English composition for his roommate, Ward Stradlater, who is heading out on a date. He is distressed when he learns that Stradlater's date is Jane Gallagher, with whom Holden has been infatuated. When Stradlater returns, hours later, he fails to appreciate the deeply personal composition Holden has written for him about the baseball glove of Holden's late brother, Allie, who died from leukemia years earlier, and refuses to say whether he had sex with Jane. Enraged, Holden punches and insults him, but Stradlater easily wins the fight. Fed up with the "phonies" at Pencey Prep, Holden decides to catch a train to New York, planning to stay away from his home until Wednesday, when his parents will have received notification of his expulsion.

Holden checks into the Edmont Hotel, where he spends an evening dancing with three tourists at the lounge until he tires of them. Following a disappointing visit to a nightclub, an angst-ridden Holden agrees to have Sunny, a prostitute, visit his room. When she enters and disrobes, Holden, a virgin, experiences a change of heart, saying he only wants to talk. Annoyed, she leaves, only to return with her pimp, Maurice, who demands more money. Holden insults Maurice, Sunny takes money from Holden's wallet, and Maurice punches him in the stomach. Afterward, Holden pictures murdering Maurice with a pistol.

The next morning, Holden—increasingly depressed and desperate for personal connection—calls Sally Hayes, a familiar date (despite his characterization of her as "queen of all phonies"). They agree to meet that afternoon to attend a play at the Biltmore Theater. After the play, Holden and Sally ice skate at Rockefeller Center, where Holden rants against society and frightens Sally. He invites her to run away with him that night to live in the New England wilderness, but she declines. The conversation sours, and the two part angrily.

He then meets his old classmate Carl Luce for drinks at the Wicker Bar. Holden annoys Carl, whom he suspects of being gay, by unrelentingly questioning him about his sex life. Carl says Holden should see a psychiatrist to understand himself better. Afterwards, Holden gets drunk, awkwardly flirts with several adults, calls Sally, and runs out of money.

Nostalgic to see his younger sister Phoebe, Holden sneaks into his parents' apartment while they are out and wakes her. Though happy to see him, Phoebe quickly guesses he has been expelled and chastises him for his general aimlessness and disdain. When she asks if he cares about anything, Holden shares a fantasy (based on a mishearing of Robert Burns's Comin' Through the Rye), in which he imagines himself saving children running through a field of rye by catching them before they fall off a nearby cliff. Phoebe points out that the actual poem says, "when a body meet a body, comin' through the rye." Holden breaks down in tears, and his sister tries to console him.

As his parents return home, he slips out and visits his former English teacher, Mr. Antolini, who expresses concern that Holden is headed for "a terrible fall". Mr. Antolini advises him to begin applying himself and provides him with a place to sleep. Holden awakens to find Mr. Antolini patting his head, which he interprets as a sexual advance. He leaves and spends the rest of the night in a train-waiting room at Grand Central Terminal, sinking deeper into despair.

In the morning, having lost hope of ever finding meaningful connection in the city, he decides to head out West to live as a deaf-mute gas station attendant in a log cabin. He arranges to see Phoebe at lunchtime to explain his plan and say goodbye. When they meet up at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, she arrives with a suitcase and asks to go with him. Holden refuses, which upsets Phoebe. He tries to cheer her by allowing her to skip school at the Central Park Zoo, but she remains angry. They eventually reach the carousel, where they reconcile after he buys her a ticket. The sight of her riding the carousel fills him with happiness.

He alludes to encountering his parents that night and "getting sick", mentioning that he will be attending another academy in September. The novel ends with Holden stating that he is reluctant to say more because talk of school has made him miss his former classmates.

History

Various older stories by Salinger contain characters similar to those in The Catcher in the Rye. While at Columbia University, Salinger wrote a short story called "The Young Folks" in Whit Burnett's class; one character from this story has been described as a "thinly penciled prototype of Sally Hayes". In November 1941 he sold the story "Slight Rebellion off Madison", which featured Holden Caulfield, to The New Yorker, but it was not published until December 21, 1946, due to World War II. The story "I'm Crazy", which was published in the December 22, 1945 issue of Collier's, contained material that was later used in The Catcher in the Rye. In 1946, The New Yorker accepted a 90-page manuscript about Holden Caulfield for publication, but Salinger later withdrew it. The school Holden attends is Pencey Preparatory Academy, a boarding school in Pennsylvania that Salinger may have based on the Valley Forge Military Academy and College.

Writing style

The Catcher in the Rye is narrated in a subjective style from the point of view of Holden Caulfield, following his exact thought processes. There is flow in the seemingly disjointed ideas and episodes; for example, as Holden sits in a chair in his dorm, minor events, such as picking up a book or looking at a table, unfold into discussions about experiences.

Critical reviews affirm that the novel accurately reflected the teenage colloquial speech of the time. Words and phrases that appear frequently include:

"Flitty" – homosexual

"Give her the time" – sexual intercourse

"Necking" – kissing, hugging, and caressing passionately

"Phony" – people who are dishonest or fake about who they really are

"Prince" – a fine, generous, helpful fellow (often used in sarcastic fashion)

"Rubbernecks" – people who turn their heads to gaze in curiosity

"Snowing" – deceiving, misleading, or winning over by glib talk, flattery, etc.

Interpretations

Bruce Brooks held that Holden's attitude remains unchanged at story's end, implying no maturation, thus differentiating the novel from young adult fiction. In contrast, Louis Menand thought that teachers assign the novel because of the optimistic ending, to teach adolescent readers that "alienation is just a phase." While Brooks maintained that Holden acts his age, Menand claimed that Holden thinks as an adult, given his ability to accurately perceive people and their motives. Others highlight the dilemma of Holden's state, in between adolescence and adulthood. Holden is quick to become emotional. "I felt sorry as hell for..." is a phrase he often uses. It is often said that Holden changes at the end, when he watches Phoebe on the carousel, and he talks about the golden ring and how it's good for kids to try to grab it.

Peter Beidler in his A Reader's Companion to J. D. Salinger's "The Catcher in the Rye" identified the movie that the prostitute "Sunny" refers to. In chapter 13 she says that in the movie a boy who looked like Holden fell off a boat, and from this detail, Beidler deduced that the movie was Captains Courageous (1937), with the boy played by child-actor Freddie Bartholomew.

Each Caulfield child has literary talent. D.B. writes screenplays in Hollywood; Holden also reveres D.B. for his writing skill (Holden's own best subject), but he also despises Hollywood industry-based movies, considering them the ultimate in "phony" as the writer has no space for his own imagination and describes D.B.'s move to Hollywood to write for films as "prostituting himself"; Allie wrote poetry on his baseball glove; and Phoebe is a diarist. This "catcher in the rye" is an analogy for Holden, who admires in children attributes that he often struggles to find in adults, like innocence, kindness, spontaneity, and generosity. Falling off the cliff could be a progression into the adult world that surrounds him and that he strongly criticizes. Later, Phoebe and Holden exchange roles as the "catcher" and the "fallen"; he gives her his hunting hat, the catcher's symbol, and becomes the fallen as Phoebe becomes the catcher.

In their biography of Salinger, David Shields and Shane Salerno argue that: "The Catcher in the Rye can best be understood as a disguised war novel." Salinger witnessed the horrors of World War II, but rather than writing a combat novel, Salinger, according to Shields and Salerno, "took the trauma of war and embedded it within what looked to the naked eye like a coming-of-age novel."

Reception

The Catcher in the Rye has been consistently listed as one of the best novels of the twentieth century. Shortly after its publication, in an article for The New York Times, Nash K. Burger called it "an unusually brilliant novel," while James Stern wrote an admiring review of the book in a voice imitating Holden's. George H. W. Bush called it a "marvelous book," listing it among the books that inspired him. In June 2009, the BBC's Finlo Rohrer wrote that, 58 years since publication, the book is still regarded "as the defining work on what it is like to be a teenager." Adam Gopnik considers it one of the "three perfect books" in American literature, along with Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and The Great Gatsby, and believes that "no book has ever captured a city better than Catcher in the Rye captured New York in the fifties." In an appraisal of The Catcher in the Rye written after the death of J. D. Salinger, Jeff Pruchnic says the novel has retained its appeal for many generations. Pruchnic describes Holden as a "teenage protagonist frozen midcentury but destined to be discovered by those of a similar age in every generation to come." Bill Gates said that The Catcher in the Rye is one of his favorite books, as has Aaron Sorkin.

Not all reception has been positive. The book has had its share of naysayers, including the longtime Washington Post book critic Jonathan Yardley, who, in 2004, wrote that the experience of rereading the novel after several decades proved to be "a painful experience: The combination of Salinger's execrable prose and Caulfield's jejune narcissism produced effects comparable to mainlining castor oil." Yardley described the novel as among the worst popular books in the annals of American literature. "Why," Yardley asked, "do English teachers, whose responsibility is to teach good writing, repeatedly and reflexively require students to read a book as badly written as this one?" According to Rohrer, many contemporary readers, as Yardley found, "just cannot understand what the fuss is about.... many of these readers are disappointed that the novel fails to meet the expectations generated by the mystique it is shrouded in. J. D. Salinger has done his part to enhance this mystique. That is to say, he has done nothing." Rohrer assessed the reasons behind both the popularity and criticism of the book, saying that it "captures existential teenage angst" and has a "complex central character" and "accessible conversational style"; while at the same time some readers may dislike the "use of 1940s New York vernacular" and the excessive "whining" of the "self-obsessed character".

Censorship in the United States

In 1960, a teacher in Tulsa, Oklahoma, was fired for assigning the novel in class. She was later reinstated. Between 1961 and 1982, The Catcher in the Rye was the most censored book in high schools and libraries in the United States. The book was briefly banned in the Issaquah, Washington, high schools in 1978 when three members of the School Board alleged the book was part of an "overall communist plot". This ban did not last long, and the offended board members were immediately recalled and removed in a special election. In 1981, it was both the most censored book and the second most taught book in public schools in the United States. According to the American Library Association, The Catcher in the Rye was the 10th most frequently challenged book from 1990 to 1999. It was one of the ten most challenged books of 2005, and although it had been off the list for three years, it reappeared in the list of most challenged books of 2009.

The challenges generally begin with Holden's frequent use of vulgar language; other reasons include sexual references, blasphemy, undermining of family values and moral codes, encouragement of rebellion, and promotion of drinking, smoking, lying, promiscuity, and sexual abuse. The book was written for an adult audience, which often forms the foundation of many challengers' arguments against it. Often the challengers have been unfamiliar with the plot itself. Shelley Keller-Gage, a high school teacher who faced objections after assigning the novel in her class, noted that "the challengers are being just like Holden... They are trying to be catchers in the rye." Censorship of the book often causes a Streisand effect, as such incidents cause many to put themselves on the waiting list to borrow the novel, where there was no waiting list before.

Violent reactions

Further information: The Catcher in the Rye in popular culture § Shootings

Several shootings have been associated with Salinger's novel, including Robert John Bardo's murder of Rebecca Schaeffer and John Hinckley Jr.'s assassination attempt on Ronald Reagan. Additionally, after fatally shooting John Lennon, Mark David Chapman was arrested with a copy of the book that he had purchased that same day, inside of which he had written: "To Holden Caulfield, From Holden Caulfield, This is my statement".

Commenting on the fascination of Hinckley and Chapman, Harvey Solomon-Brady wrote:

Compared to books lauded by other killers – George Orwell's 1984 by John F. Kennedy's assassin Lee Harvey Oswald, C.S. Lewis's meditations on Christianity by Gianni Versace's murderer Andrew Cunanan and Joseph Conrad's The Secret Agent by Unabomber Ted Kaczynski – The Catcher in the Rye stands out in its devastating ability to influence without explicit instruction.

Attempted adaptations

In film

Early in his career, Salinger expressed a willingness to have his work adapted for the screen. In 1949, a critically panned film version of his short story "Uncle Wiggily in Connecticut" was released; renamed My Foolish Heart, the film took great liberties with Salinger's plot and is widely considered to be among the reasons that Salinger refused to allow any subsequent film adaptations of his work. The enduring success of The Catcher in the Rye, however, has resulted in repeated attempts to secure the novel's screen rights.

When The Catcher in the Rye was first released, many offers were made to adapt it for the screen, including one from Samuel Goldwyn, producer of My Foolish Heart. In a letter written in the early 1950s, Salinger spoke of mounting a play in which he would play the role of Holden Caulfield opposite Margaret O'Brien, and, if he couldn't play the part himself, to "forget about it." Almost 50 years later, the writer Joyce Maynard definitively concluded, "The only person who might ever have played Holden Caulfield would have been J. D. Salinger."

Salinger told Maynard in the 1970s that Jerry Lewis "tried for years to get his hands on the part of Holden," the protagonist in the novel which Lewis had not read until he was in his thirties. Film industry figures including Marlon Brando, Jack Nicholson, Ralph Bakshi, Tobey Maguire and Leonardo DiCaprio have tried to make a film adaptation. In an interview with Premiere, John Cusack commented that his one regret about turning 21 was that he had become too old to play Holden Caulfield. Writer-director Billy Wilder recounted his abortive attempts to snare the novel's rights:

Of course I read The Catcher in the Rye... Wonderful book. I loved it. I pursued it. I wanted to make a picture out of it. And then one day a young man came to the office of Leland Hayward, my agent, in New York, and said, "Please tell Mr. Leland Hayward to lay off. He's very, very insensitive." And he walked out. That was the entire speech. I never saw him. That was J. D. Salinger and that was Catcher in the Rye.

In 1961, Salinger denied Elia Kazan permission to direct a stage adaptation of Catcher for Broadway. Later, Salinger's agents received bids for the Catcher film rights from Harvey Weinstein and Steven Spielberg, neither of which was even passed on to Salinger for consideration.

In 2003, the BBC television program The Big Read featured The Catcher in the Rye, interspersing discussions of the novel with "a series of short films that featured an actor playing J. D. Salinger's adolescent antihero, Holden Caulfield." The show defended its unlicensed adaptation of the novel by claiming to be a "literary review", and no major charges were filed.

In 2008, the rights of Salinger's works were placed in the JD Salinger Literary Trust where Salinger was the sole trustee. Phyllis Westberg, who was Salinger's agent at Harold Ober Associates in New York, declined to say who the trustees are now that the author is dead. After Salinger died in 2010, Westberg stated that nothing had changed in terms of licensing film, television, or stage rights of his works. A letter written by Salinger in 1957 revealed that he was open to an adaptation of The Catcher in the Rye released after his death. He wrote: "Firstly, it is possible that one day the rights will be sold. Since there's an ever-looming possibility that I won't die rich, I toy very seriously with the idea of leaving the unsold rights to my wife and daughter as a kind of insurance policy. It pleasures me no end, though, I might quickly add, to know that I won't have to see the results of the transaction." Salinger also wrote that he believed his novel was not suitable for film treatment, and that translating Holden Caulfield's first-person narrative into voice-over and dialogue would be contrived.

In 2020, Don Hahn revealed that The Walt Disney Company had almost made an animated film titled Dufus which would have been an adaptation of The Catcher in the Rye "with German shepherds", most likely akin to Oliver & Company. The idea came from then CEO Michael Eisner who loved the book and wanted to do an adaptation. After being told that J. D. Salinger would not agree to sell the film rights, Eisner stated, "Well, let's just do that kind of story, that kind of growing up, coming of age story."

Banned fan sequel

In 2009, the year before he died, Salinger successfully sued to stop the U.S. publication of a novel that presents Holden Caulfield as an old man. The novel's author, Fredrik Colting, commented: "call me an ignorant Swede, but the last thing I thought possible in the U.S. was that you banned books". The issue is complicated by the nature of Colting's book, 60 Years Later: Coming Through the Rye, which has been compared to fan fiction. Although commonly not authorized by writers, no legal action is usually taken against fan fiction, since it is rarely published commercially and thus involves no profit.

Legacy and use in popular culture

Main article: The Catcher in the Rye in popular culture

See also

Book censorship in the United States

Le Monde's 100 Books of the Century

…

Battle on the Ice

1242 battle of the Northern Crusades on the frozen Lake Peipus

Not to be confused with Battle on the Ice of Lake V;nern.

For other battles on ice, see List of military operations on ice.

The Battle on the Ice, also known as the Battle of Lake Peipus (‹See Tfd›German: Schlacht auf dem Peipussee) or Battle of Lake Chud (‹See Tfd›Russian: битва на Чудском озере, romanized: bitva na Chudskom ozere), took place on 5 April 1242. It was fought on or near the frozen Lake Peipus between the united forces of the Republic of Novgorod and Vladimir-Suzdal, led by Prince Alexander Nevsky, and the forces of the Livonian Order and Bishopric of Dorpat, led by Bishop Hermann of Dorpat.

Quick Facts Battle on the Ice, Date ...

The outcome of the battle has been interpreted as significant for the balance of power between Western Catholicism and Eastern Orthodox Christianity. In the end, the battle represented a significant defeat for the Catholic forces during the Northern Crusades, bringing an end to their campaigns against the Orthodox Novgorod Republic and other Rus' territories for the next century.

Pope Honorius III (1216–1227) received a number of petitions regarding new Baltic crusades, mainly concerning Prussia and Livonia but also a report from the Swedish Archbishop concerning difficulties with their mission in Finland. At that time, Honorius responded to the Swedish Archbishop only by declaring an embargo against trade with pagans in the region; it is not known if the Swedes requested further help for the moment.

In 1237, the Swedes received papal authorization to launch a crusade, and in 1240, new campaigns began in the easternmost part of the Baltic region. The Finnish mission's eastward expansion led to a clash between Sweden and Novgorod, since the Karelians had been allies and tributaries of Novgorod since the mid-12th century. After a successful campaign into Tavastia, the Swedes advanced further east until they were stopped by a Novgorodian army led by Prince Alexander Yaroslavich who defeated the Swedes in the Battle of the Neva in July 1240 and received the nickname Nevsky. Novgorod fought against the crusade for economic reasons, to protect their monopoly of the Karelian fur trade.

In Livonia, although the missionaries and Crusaders had attempted to establish peaceful relations with the Novgorod Republic, Livonian missionary and crusade activity in Estonia caused conflicts with Novgorod: Novgorod had also attempted to subjugate, raid and convert the pagan Estonians. The Estonians would also sometimes ally with various Russian principalities against the crusaders, since the eastern Baltic missions also constituted a threat to Russian interests and the tributary peoples. In 1240, the combined forces of the exiled prince of Pskov, Yaroslav Vladimirovich, and men from the Bishopric of Dorpat attacked the Pskov Land and Votia, a tributary of Novgorod. This triggered the counterattack from Novgorod in 1241. The delayed response was a result of the internal strife in Novgorod.

Hoping to exploit Novgorod's weakness in the wake of the Mongol and Swedish invasions, the Teutonic Knights attacked the neighboring Novgorod Republic and occupied Pskov, Izborsk, and Koporye in the autumn of 1240. When they approached Novgorod itself, the local citizens recalled to the city 20-year-old Prince Alexander Nevsky, whom they had banished to Pereslavl earlier that year.

In regards to the pagans still living between Pskov and Novgorod and the Latin Christian settlements in Finland, Estonia and Livonia ("the land between christianized Estonia and Russia, meaning Votia, Neva, Izhoria, and Karelia"), a treaty was concluded in 1241 at Riga between the bishop of ;sel–Wiek and the Teutonic Order, which stipulated that the bishop was granted spiritual superiority in the newly conquered territories. The treaty indicated that the crusaders were well aware of the existence of these pagans.

During the campaign of 1241, Alexander managed to retake Pskov and Koporye from the crusaders, and executed those local Votians who had worked with the invaders. Alexander then continued into Estonian-German territory. In the spring of 1242, the Teutonic Knights defeated a detachment of the Novgorodian army about 20 kilometres (12 mi) south of the fortress of Dorpat (now Tartu). As a result, Alexander set up a position at Lake Peipus. Led by Prince-Bishop Hermann of Dorpat, the knights and their auxiliary troops of local Ugaunians then met with Alexander's forces on 5 April 1242, by the narrow strait (Lake L;mmij;rv or Teploe) that connects the north and south parts of Lake Peipus (Lake Peipus proper with Lake Pskovskoye).[citation needed]

According to the Livonian Order's Livonian Rhymed Chronicle (written in the 1290s):

...But they had brought along too few people, and the Brothers' army was also too small. Nevertheless they decided to attack the Rus' [R;;en]. The latter had many archers. The battle began with their bold assault on the king's men [Danes]. The Brothers' banners were soon flying in the midst of the archers, and swords were heard cutting helmets apart. Many from both sides fell dead on the grass [;f da; gras]. Then the Brothers' army was completely surrounded, for the Rus' had so many troops that there were easily sixty men for every one German knight. The Brothers fought well enough, but they were nonetheless cut down. Some of those from Dorpat escaped from the battle, and it was their salvation that they had been forced to flee. Twenty Brothers lay dead and six were captured. Thus the battle ended.

According to the Laurentian continuation of the Suzdalian Chronicle (compiled in 1377; the entry in question may originally have been composed around 1310):

Великъ;и кн;з; ;рославъ посла сн;а сво;го Андр;а в Новъгородъ Великъ;и в помочь ;лександрови на Н;мци. и поб;диша ; за Плесковом; на ;зер; и полонъ многъ пл;ниша. и възвратис; Андр;и къ ;ц;ю своєму с чс;тью.

Grand Prince Iaroslav sent his son Andrei to Great Novgorod in aid of Alexander against the Germans and defeated them beyond Pskov at the lake (на озере) and took many prisoners. Andrei returned to his father with honor.

According to the Synod Scroll (Older Redaction) of the Novgorod First Chronicle (the entry of which has been dated to c. 1350):

Prince Alexander and all the men of Novgorod drew up their forces by the lake, at Uzmen, by the Raven's Rock; and the Germans [Nemtsy] and the Estonians [Chuds] rode at them, driving themselves like a wedge through their army. And there was a great slaughter of Germans and Estonians... they fought with them during the pursuit on the ice seven versts short of the Subol [north-western] shore. And there fell a countless number of Estonians, and 400 of the Germans, and they took fifty with their hands and they took them to Novgorod.

The Younger Redaction of the Novgorod First Chronicle (compiled in the 1440s) increased the amount of "Germans" (Nemtsy) killed from 400 to 500.

The Life of Alexander Nevsky, the earliest redaction of which was dated by Donald Ostrowski to the mid-15th century, combined all the various elements of the Laurentian Suzdalian, Novgorod First, and Moscow Academic (Rostov-Suzdal) accounts. It was the first version to claim that the battle itself took place upon the ice of the frozen lake, that many soldiers were killed on the ice, and that the bodies of dead soldiers of both sides covered the ice with blood. It even states that 'There was ... a noise from the breaking of lances and a sound from the clanging of swords as though the frozen lake moved,' suggesting the clamor of battle somehow stirred the ice, although there is no mention of it breaking. This narration of events appears irreconcilable with the report of the Livonian Rhymed Chronicle that the dead soldiers "fell on the grass".

Scholarly reconstructions of the battle

On 5 April 1242 Alexander, intending to fight in a place of his own choosing, retreated in an attempt to draw the often over-confident Crusaders onto the frozen lake. Estimates on the number of troops in the opposing armies vary widely among scholars. A more conservative estimation by David Nicolle (1996) has it that the crusader forces likely numbered around 2,600, including 800 Danish and German knights, 100 Teutonic knights, 300 Danes, 400 Germans, and 1,000 Estonian infantry. The Novgorodians fielded around 5,000 men: Alexander and his brother Andrei's bodyguards (druzhina), totalling around 1,000, plus 2,000 militia of Novgorod, 1,400 Finno-Ugrian tribesmen, and 600 horse archers.

The Teutonic knights and crusaders charged across the lake and reached the enemy, but were held up by the infantry of the Novgorodian militia. This caused the momentum of the crusader attack to slow. The battle was fierce, with the allied Rus' soldiers fighting the Teutonic and crusader troops on the frozen surface of the lake. After a little more than two hours of close quarters fighting, Alexander ordered the left and right wings of his army (including cavalry) to enter the battle. The Teutonic and crusader troops by that time were exhausted from the constant struggle on the slippery surface of the frozen lake. The Crusaders started to retreat in disarray deeper onto the ice, and the appearance of the fresh Novgorod cavalry made them retreat in panic.[citation needed]

Historical legacy

The knights' defeat at the hands of Alexander's forces prevented the crusaders from retaking Pskov, the linchpin of their eastern crusade.[citation needed] The battle thus halted the eastward expansion of the Teutonic Order. Thereafter, the river Narva and Lake Peipus would represent a stable boundary dividing Eastern Orthodoxy from Western Catholicism.

Some historians have argued that the launch of the campaigns in the eastern Baltic at the same time were part of a coordinated campaign; Finnish historian Gustav A. Donner argued in 1929 that a joint campaign was organized by William of Modena and originated in the Roman Curia. This interpretation was taken up by Russian historians such as Igor Pavlovich Shaskol'skii and a number of Western European historians. More recent historians have rejected the idea of a coordinated attack between the Swedes, Danes and Germans, as well as a papal master plan due to a lack of decisive evidence. Some scholars have instead considered the Swedish attack on the Neva River to be part of the continuation of rivalry between the Rus' and Swedes for supremacy in Finland and Karelia. Anti Selart also mentions that the papal bulls from 1240 to 1243 do not mention warfare against "Russians", but against non-Christians. Selart also argues that the crusades were not an attempt to conquer Rus', but still constituted an attack on the territory of Novgorod and its interests.

In 1983, a revisionist view proposed by historian John L. I. Fennell argued that the battle was not as important, nor as large, as has often been portrayed. Fennell claimed that most of the Teutonic Knights were by that time engaged elsewhere in the Baltic, and that the apparently low number of knights' casualties according to their own sources indicates the smallness of the encounter. He also says that neither the Suzdalian Chronicle (the Lavrent'evskiy), nor any of the Swedish sources mention the occasion, which according to him would mean that the 'great battle' was little more than one of many periodic clashes. In 2000, Russian historian Aleksandr Uzhankov suggested that Fennell distorted the picture by ignoring many historical facts and documents. To stress the importance of the battle, he cites two papal bulls of Gregory IX, promulgated in 1233 and 1237, which called for a crusade to protect Christianity in Finland against her neighbours. The first bull explicitly mentions Russia. The kingdoms of Sweden, Denmark and the Teutonic Order built up an alliance in June 1238, under the auspices of the Danish king Valdemar II. They assembled the largest western cavalry force of their time. Another point mentioned by Uzhankov is the 1243 treaty between Novgorod and the Teutonic Order, where the knights abandoned all claims to Russian lands. Uzhankov also emphasizes, with respect to the scale of battle, that for each knight deployed on the field there were eight to 30 combatants, counting squires, archers and servants (though at his stated ratios, that would still make the Teutonic losses number at most a few hundred).[better source needed]

Cultural legacy

Tsarist Russia

Alexander was canonised as a saint in the Russian Orthodox Church in 1574.[citation needed]

Soviet Russia and breaking ice in 1938 film Alexander Nevsky

In the 1938 film Alexander Nevsky, Novgorodians chase Teutonic knights across the frozen lake; the ice breaks, and many Teutons drown.

The event was glorified in Sergei Eisenstein's patriotic historical drama film Alexander Nevsky, released in 1938. The movie, bearing propagandist allegories of the Teutonic Knights as Nazi Germans, with the Teutonic infantry wearing modified World War I German Stahlhelm helmets, has created a popular image of the battle often mistaken for the real events. In particular, the image of knights dying by breaking the ice and drowning originates from the film. Sergei Prokofiev turned his score for the film into a concert cantata of the same title, the longest movement of which is "The Battle on the Ice". The editors of the 1977 English translation of the Livonian Rhymed Chronicle, Jerry Smith and William Urban, commented that 'Eisenstein's movie Alexander Nevsky is magnificent and worth seeing, but he tells us more about 1939 than 1242.'

The 1938 film created the popular misconception that "the Teutonic knights and crusaders attempted to rally and regroup at the far side of the lake, however, the thin ice began to give way and cracked under the weight of their heavy armour, and many knights and crusaders drowned."[citation needed] However, Donald Ostrowski writes in his 2006 article Alexander Nevskii's "Battle on the Ice": The Creation of a Legend that accounts of ice breaking and knights drowning are a relatively recent embellishment to the original historical story. None of the primary sources mention ice breaking; the earliest account in the LRC explicitly says killed soldiers "fell on the grass" and the Laurentian continuation that it was "at a lake beyond Pleskov" (rather than "on a lake"). It was not until decades later that more details were gradually added of a specific lake, that the lake was frozen, that the crusaders were supposedly chased across the frozen lake, and not until the 15th century that a battle (not just a chase) allegedly took place on the ice itself. He cites a large number of scholars who have written about the battle, Karamzin, Solovyev, Petrushevskii, Khitrov, Platonov, Grekov, Vernadsky, Razin, Myakotin, Pashuto, Fennell, and Kirpichnikov, none of whom mention the ice breaking up or anyone drowning when discussing the battle of Lake Peipus. After analysing all the sources, Ostrowski concludes that the part about ice breaking and drowning appeared first in the 1938 film Alexander Nevsky by Sergei Eisenstein.

During World War II, the image of Alexander Nevsky became a national Soviet Russian symbol of the struggle against German occupation. The Order of Alexander Nevsky was re-established in the Soviet Union in 1942 during the Great Patriotic War.[citation needed]

Russian Federation

Battle of the Ice anniversary, 750 years. Russian postage stamps, 1992

The Novgorodian victory is commemorated today[when?] in Russia as one of the Days of Military Honour.[citation needed]

Since 2010, the Russian government has given out an Order of Alexander Nevsky (originally introduced by Catherine I of Russia in 1725) given for outstanding bravery and excellent service to the country.[citation needed]

Notes

‹See Tfd›German: Schlacht auf dem Eise; ‹See Tfd›Russian: Ледовое побоище, romanized: Ledovoye poboishche; Estonian: J;;lahing.

"inter Estoniamiam conversam et Rutiam, in terris videlicet Watlande, Nouve, Ingriae et Carelae, de quibus spes erat conversionis ad fidem Christi".

"sie haten ze cleine volkes br;cht; der bruoder her was ouch ze clein. iedoch sie qu;men ;ber ein, daz sie die Riuzen riten an: str;tes man mit in began. die Riuzen hatten sch;tzen vil, die huoben d; daz ;rste spil m;nlich v;r des k;neges schar. man sach der bruoder banier dar die sch;tzen under dringen, man h;rte schwert d; clingen und sach helme schr;ten. an beider s;t die t;ten vielen nider ;f das gras. Wer in der bruoder her was die wurden umbe ringet gar. die Riuzen hatten solhe schar, daz ie wol sechzic man einen diutschen riten an. die bruoder t;ten wer genuoc, iedoch man sie dar nider sluoc, der von Darbete quam ein teil von dem str;te, daz war ir heil: sie muosten wichen durch die n;t. d; bliben zweinzic bruoder t;t und sechse wurden gevangen. sus was der str;t ergangen."

Bibliography

Primary sources

Life of Alexander Nevsky (c. 1450).

Livonian Rhymed Chronicle (LRC, c. 1290s).

Livl;ndische Reimchronik. Mit Anmerkungen, Namenverzeichnis und Glossar. Ed. Leo Meyer. Paderborn 1876 (Reprint: Hildesheim 1963). (in German)

Smith, Jerry C.; Urban, William L., eds. (1977). The Livonian Rhymed Chronicle: Translated with an Historical Introduction, Maps and Appendices. Uralic and Altaic series. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-87750-213-5.

Pskov Third Chronicle (1567).

Savignac, David (2016). The Pskov 3rd Chronicle. 2nd Edition. Edited, translated, and annotated by David Savignac. Crofton: Beowulf & Sons. p. 245. Retrieved 17 September 2024. Entries under the years 1240–1242. Translation based on the 2000 reprint of Nasonov's 1955 critical edition of the Pskov Chronicles.

"Rostov-Suzdal Compilation" in the Moscow Academic Chronicle (MAk, c. 1500).

Suzdalian Chronicle, Laurentian continuation (1377), s.a. 6750 (1242).

Лаврентьевская летопись [Laurentian Chronicle]. Полное Собрание Русских Литописей [Complete Collection of Rus' Chronicles] (in Church Slavic). Vol. 1. Leningrad: USSR Academy of Sciences Publishing House. 1926–1928.

Synod Scroll (Older Redaction) of the Novgorod First Chronicle (c. 1275), s.a. 6750 (1242).

Michell, Robert; Forbes, Nevill (1914). The Chronicle of Novgorod 1016–1471. Translated from the Russian by Robert Michell and Nevill Forbes, Ph.D. Reader in Russian in the University of Oxford, with an introduction by C. Raymond Beazley and A. A. Shakhmatov (PDF). London: Gray's Inn. p. 237. Retrieved 5 April 2024.

Literature

Fonnesberg-Schmidt, Iben (2007). The popes and the Baltic crusades, 1147–1254. Brill. ISBN 9789004155022.

Hellie, Richard (2006). "Alexander Nevskii's April 5, 1242 Battle on the Ice". Russian History/Histoire Russe. 33 (2/4). Brill: 283–287. doi:10.1163/187633106X00177. JSTOR 24664445 – via JSTOR.

Martin, Janet (2007). Medieval Russia: 980–1584. Second Edition. E-book. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-511-36800-4.

Murray, Alan V. (2017). Crusade and Conversion on the Baltic Frontier 1150–1500. Taylor & Francis. p. 326. ISBN 978-1-351-94715-2.

Nicolle, David (1996). Lake Peipus 1242: Battle of the Ice. Osprey Publishing. p. 41. ISBN 9781855325531.

Ostrowski, Donald (2006). "Alexander Nevskii's 'Battle on the Ice': The Creation of a Legend". Russian History/Histoire Russe. 33 (2/4). Brill: 289–312. ISSN 0094-288X. JSTOR 24664446.

References

[1]

Nicolle 1996, p. 41.

[2]

Michell & Forbes 1914, p. 87.

[3]

The New Encyclopaedia Britannica. Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2003. p. 241. ISBN 978-0-85229-961-6.

[4]

Fonnesberg-Schmidt 2007, p. 136.

[5]

Fonnesberg-Schmidt 2007, pp. 216–217, In 1240 new campaigns were launched... first was organized by the Swedes... obtained papal authorization in 1237.

[6]

Fonnesberg-Schmidt 2007, pp. 216–217, The Russian victory was later depicted as an event of great national importance and Prince Alexander was given the sobriquet "Nevskii".

[7]

Andrew Jotischky (2017). Crusading and the Crusader States. Taylor and Francis. p. 220. ISBN 9781351983921.

[8]

Martin 2007, pp. 175–219.

[9]

Fonnesberg-Schmidt 2007, p. 216, The missions in the eastern Baltic constituted a threat to the Russians of Novgorod and Pskov, their tributary peoples and their interests in the region..

[10]

Fonnesberg-Schmidt 2007, p. 220, The campaigns to the River Neva and into Votia were... crusades aiming at expanding the Catholic Church... the campaign against Izborsk and Pskov was a purely political undertaking... the co-operation between the exiled Prince Yaroslav Vladimirovich of Pskov and the men from the bishopric of Dorpat..

[11]

Fonnesberg-Schmidt 2007, pp. 218, In the winter of 1240–41, a group of Latin Christians invaded Votia, the lands north-east of Lake Peipus which were tributary to Novgorod..

[12]

Fonnesberg-Schmidt 2007, p. 218, The Novgorodian counterattack came in 1241..

[13]

Fonnesberg-Schmidt 2007, p. 218.

[14]

Hellie 2006, p. 284.

[15]

Fonnesberg-Schmidt 2007, p. 220.

[16]

Murray 2017, p. 164.

[17]

Fonnesberg-Schmidt 2007, p. 218, After pleas from Novgorod Alexander returned in 1241 and marched against Kopor'e. Having conquered the fortress and captured the remaining Latin Christians, he executed those local Votians who had cooperated with the invaders..

[18]

Murray 2017, p. 164, These conquests were lost in 1241–42, when the Russians destroyed Kopor'e..

[19]

Ostrowski 2006, p. 291.

[20]

Smith & Urban 1977, pp. 31–32.

[21]

Ostrowski 2006, p. 293.

[22]

"Въ лЂто 6745 [1237] — въ лЂто 6758 [1250]. Лаврентіївський літопис" [In the year 6745 [1237] – 6758 [1250]. The Laurentian Codex]. litopys.org.ua (in Church Slavic). 1928. Retrieved 17 September 2024.

[23]

Christiansen, Eric (4 December 1997). The Northern Crusades. Penguin UK. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-14-193736-6.

[24]

Ostrowski 2006, p. 298.

[25]

Ostrowski 2006, pp. 298–299.

[26]

Ostrowski 2006, pp. 299–300.

[27]

Ostrowski 2006, p. 300.

[28]

Riley-Smith Jonathan Simon Christopher. The Crusades: a History, US, 1987, ISBN 0300101287, p. 198.

[29]

Hosking, Geoffrey A. Russia and the Russians: a history, US, 2001, ISBN 0674004736, p. 65.

[30]

Fonnesberg-Schmidt 2007, p. 219.

[31]

Fonnesberg-Schmidt 2007, p. 219, Some scholars therefore regard the Swedish attack on the River Neva as merely a continuation of the Russo-Swedish rivalry..

[32]

Fonnesberg-Schmidt 2007, pp. 219–220, Selart stresses, none of the papal bulls of 1240–43 mention warfare against the Russians. They only refer to the fight against non-Christians and to mission among pagans.

[33]

Selart, Anti (2001). "Confessional Conflict and Political Co-operation: Livonia and Russia in the Thirteenth Century". Crusade and Conversion on the Baltic Frontier 1150–1500. Routledge. pp. 151–176. doi:10.4324/9781315258805-8. ISBN 978-1-315-25880-5.

[34]

John Fennell, The Crisis of Medieval Russia 1200–1304, (London: Longman, 1983), 106.[ISBN missing]

[35]

Александр Ужанков. Меж двух зол. Исторический выбор Александра Невского (Alexander Uzhankov. Between two evils. The historical choice of Alexander Nevsky) (in Russian)

[36]

"Alexander Nevsky and the Rout of the Germans". The Eisenstein Reader: 140–144. 1998. doi:10.5040/9781838711023.ch-014. ISBN 9781838711023.

[37]

Ostrowski 2006, pp. 289–312.

[38]

Danilevsky, Igor (22 May 2015). Ледовое побоище (in Russian). Postnauka. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

[39]

Smith & Urban 1977, p. 32.

[40]

Ostrowski 2006, p. 299.

[41]

Ostrowski 2006, p. 294.

[42]

Ostrowski 2006, pp. 295–296.

Further reading

Military Heritage did a feature on the Battle of Lake Peipus and the holy Knights Templar and the monastic knighthood Hospitallers (Terry Gore, Military Heritage, August 2005, Volume 7, No. 1, pp. 28–33), ISSN 1524-8666.

Basil Dmytryshyn, Medieval Russia 900–1700. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1973.

John France, Western Warfare in the Age of the Crusades 1000–1300. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1999.

Terrence Wise, The Knights of Christ. London: Osprey Publishing, 1984.

Dittmar Dahlmann Der russische Sieg ;ber die „teutonischen Ritter“ auf dem Peipussee 1242. In: Gerd Krumeich, Susanne Brandt (ed.): Schlachtenmythen. Ereignis–Erz;hlung–Erinnerung. B;hlau, K;ln/Wien 2003, ISBN 3412087033, pp. 63–75. (in German)

Anti Selart. Livland und die Rus' im 13. Jahrhundert. B;hlau, K;ln/Wien 2012, ISBN 9783412160067. (in German)

Anti Selart. Livonia, Rus’ and the Baltic Crusades in the Thirteenth Century. Brill, Leiden/Boston, 2015.

Kaldalu, Meelis; Toots, Timo, Looking for the Border Island. Tartu: Damtan Publishing, 2005. Contemporary journalistic narrative about an Estonian youth attempting to uncover the secret of the Ice Battle.

Joseph Brassey, Cooper Moo, Mark Teppo, Angus Trim, "Katabasis (The Mongoliad Cycle Book 4)" 47 North, 2013 ISBN 1477848215

==External links==

{{Commons category}}

* J;;LAHING 1242 ; Episood 1/4. Kes lasi t;de j;lle sedapidi paista?] at ''[[Postimees]]'' (in Estonian)

{{Coord|58|14|N|27|30|E|display=title}}

{{Authority control}}

[[Category:1242 in Europe]]

[[Category:Battles involving the Novgorod Republic|Ice 1242]]

[[Category:Battles involving the Livonian Order|Ice 1242]]

[[Category:Battles involving the Teutonic Order|Ice 1242]]

[[Category:Conflicts in 1242|Ice]]

[[Category:Battles involving Denmark|Ice]]

[[Category:History of Pskov Oblast]]

[[Category:13th century in Estonia]]

[[Category:13th century in Russia]]

…

Жить не по лжи!

Добавление краткого описания

«Жить не по лжи!» — публицистическое эссе Александра Солженицына, обращённое к советской интеллигенции. Тематически примыкает к эссе «На возврате дыхания и сознания», «Раскаяние и самоограничение как категории национальной жизни», «Образованщина», вышедшим в том же году в сборнике «Из-под глыб». Опубликовано в самиздате 13 февраля 1974 года (при публикации датировано предыдущим днём — днём ареста Солженицына).

Краткие факты Жить не по лжи!, Жанр ...

Содержание

Солженицын в этом эссе призывал каждого поступать так, чтобы из-под его пера не вышло ни единой фразы, «искривляющей правду», не высказывать подобной фразы ни устно, ни письменно, не цитировать ни единой мысли, которую он искренне не разделяет, не участвовать в политических акциях, которые не отвечают его желанию, не голосовать за тех, кто недостоин быть избранным. Кроме того, Солженицын предлагал наиболее доступный, по его мнению, способ борьбы с режимом:

Самый доступный ключ к нашему освобождению: личное неучастие во лжи! Пусть ложь всё покрыла, всем владеет, но в самом малом упрёмся: пусть владеет не через меня!

История написания и публикации

Воззвание «Жить не по лжи!» Солженицын писал в 1972 году, возвращался к тексту в 1973-м — окончательный вариант был готов к сентябрю. Автор предполагал обнародовать статью одновременно с «Письмом вождям Советского Союза», но в сентябре 1973-го, узнав о захвате «Архипелага ГУЛАГ» Комитетом госбезопасности, с риском для жизни принял решение публиковать книгу на Западе. Статья «Жить не по лжи!» была отложена как «запасной выстрел», на случай ареста или смерти. Текст был помещён в несколько тайников с уговором — в случае ареста «пускать» через сутки, не ожидая подтверждения от автора.

История «запуска» воззвания в печать описана Солженицыным в книге «Бодался телёнок с дубом», писатель реконструирует чувства жены на следующий день после его ареста 12 февраля 1974 года, когда о его судьбе было ничего не известно:

«…набегают вопросы, а голова помрачённая. Что делать с Завещанием-программой? А — с „Жить не по лжи“? Оно заложено на несколько стартов, должно быть пущено, когда с автором случится: смерть, арест, ссылка.

Но — что случилось сейчас? Ещё в колебании? ещё клонится? Ещё есть ли арест?

А может, уже и не жив? Э-э, если уж пришли, так решились. Только атаковать!

Пускать! И метить вчерашней датой. (Пошло через несколько часов.) Тут звонит из Цюриха адвокат Хееб[нем.]: „Чем может быть полезен мадам Солженицыной?“

Сперва — даже смешно, хотя трогательно: чем же он может быть полезен?! Вдруг просверкнуло: да конечно же! Торжественно в телефон: „Прошу доктора Хееба немедленно приступить к публикации всех до сих пор хранимых произведений Солженицына!“ — пусть слушает ГБ!..»

Обращение писателя к соотечественникам тут же появилось в самиздате, помеченное датой ареста — 12 февраля 1974 года. В ту же ночь, с 12 на 13 февраля, через иностранных корреспондентов текст был передан на Запад. 18 февраля 1974 года эссе было опубликовано в газете «Daily Express» (Лондон), на русском языке — в парижском журнале «Вестник РСХД» (1973 [реально вышел в 1974]. № 108/110. С. 1—3), газетах «Новое русское слово» (Нью-Йорк. 1974. 16 марта), «Русская мысль» (Париж. 1974. 21 марта. С. 3), журнале «Посев» (Франкфурт-на-Майне. 1974. № 3. С. 8—10).

Заголовок статьи (без восклицательного знака) дал название вскоре появившемуся в самиздате, а затем изданному в Париже сборнику материалов, посвящённому выходу в свет книги «Архипелаг ГУЛАГ» (Жить не по лжи: сб. мат-лов. Август 1973 — февраль 1974. Самиздат — Москва. — Paris: YMCA-Press, 1975; сама статья завершала сборник).

Впервые (неофициально, без ведома автора) в СССР было опубликовано 18 октября 1988 года в киевской газете «Рабочее слово» (Дорпрофсож ЮЗЖД).

На основе идей эссе создано слово «неполживый», применяемое к российским сторонникам либерализма.

См. также

Наши плюралисты

…

15 песен Гребенщикова, которые теперь будут вне закона

И это не «Вечерний М»! Как известно, 30 октября в Госдуму был внесён законопроект об уголовной ответственности за пропаганду наркотиков. Максимальный срок - 7 лет лишения свободы. "Под пропагандой либо незаконной рекламой наркотических средств понимается деятельность по распространению материалов и (или) информации, направленных на формирование у лица нейтрального, терпимого либо положительного отношения к таким средствам…" - говорится в документе.

При этом, сами депутаты категорически отказались тестироваться на наркотики. Законопроект об обязательных проверках госслужащих, сенаторов и депутатов на употребление наркотиков отклонён в первом же чтении и снят с дальнейшего рассмотрения. Ну да ладно, иного ожидать, в общем-то, и не приходилось.

А что, если вся эта история распространится не только на интернет-контент, но и на литературу, музыку, театр, кино и так далее? Вероятность весьма велика! Ну хотя бы потому, что антинаркотическую уголовку горячо одобрил сам президент.

Давайте навскидку пройдёмся... ну хотя бы по музыке. По нестареющей классике, так сказать. Только гляньте, сколько всего запросто может оказаться криминальным. Возьмём к примеру Бориса нашего Борисовича. Итак...

1.

"А я сижу на крыше и я очень рад.

Я сижу на крыше и я истинно рад.

Потребляю сенсимилью как аристократ..."

Песня "Аристократ", 1982.

2.

"Мы встретились в 73-м,

коллеги на Алмазном Пути.

У тебя тогда был сквот в Лувре,

там еще внизу был склад DMT"

Песня "Зимняя роза", 2003.

3.

"А как по Волге ходит одинокий бурлак,

Ходит бечевой небесных равнин,

Ему господин кажет с неба кулак,

А ему все смешно — в кулаке кокаин..."

Песня "Бурлак", 1991.

4.

"На льду Бел-озера один на один

сошлись наш ангел алкоголь и их демон кокаин..."

Песня "Скорбец", 1998.

5.

"Хэй, кто-нибудь помнит, кто висит на кресте?

Праведников колбасит, как братву на кислоте..."

Песня "500", 2001.

6.

"Где летучие рыбы сами прыгают в рот,

Ну, другими словами, фэн-шуй да не тот,

У нее женский бизнес,

Он танцует и курит грибы..."

Песня "Нога судьбы", 2001.

7.

"В Сан-Франциско, на улице Индианы

Растут пальмы марихуаны.

Эти пальмы неземной красоты,

Их охраняют голубые менты.

Мимо них фланируют бомжи-растаманы,

У которых всего полные карманы.

Льются коктейли и плещется виски,

И кружатся квадратные диски."

Песня "Вятка - Сан-Франциско", 2009.

8.

"Я удолбан весь день,

Уже лет двенадцать подряд.

Не дышите, когда я вхожу:

Я - наркотический яд.

Моё сердце из масти,

Кровь - диэтиламид;

Не надо смотреть на меня,

Потому что иначе ты вымрешь, как вид."

Песня "Таможенный блюз", 1995.

9.

"А вот и все мои товарищи - водка без хлеба,

Один брат - Сирин, а другой брат - Спас.

А третий хотел дойти ногами до неба,

Но выпил, удолбался - вот и весь сказ."

Песня "Кони беспредела", 1991.

10.

"Нам в школе выдали линейку,

чтобы мерить объем головы;

выдали линейку,

чтобы мерить объем головы.

Мама, в каникулы мы едем на Джамейку

работать над курением травы."

Песня "Растаманы из глубинки", 1998.

11.

"Между Bleeker и McDougal,

Много маленьких кафе,

А я хотел купить наркотик,

А он уехал в Санта-Фе.

Летом здесь едят пейотль,

А ЛСД едят весной.

Страсть как много телефонов

В моей книжке записной."

Песня "Нью-Йоркские страдания", 1992.

12.

"Во всей Смоленщине нет кокаина -

это временный кризис сырья.

Ты не узнаешь тех мест, где ты вырос,

когда ты придешь в себя."

Песня "По дороге в Дамаск", 1997.

13.

"Снесла мне крышу кислота,

свод небес надо мной поет тишиной,

и вся природа пуста

такой особой пустотой."

Песня "Генерал", 1987.

14.

"Столько лет все строили дом —

Наша ли вина, что пустой?

Зато теперь, мы знаем, каково с серебром;

посмотрим, каково с кислотой..."

Песня "Государыня", 1991.

15.

"А над удолбанной Москвою в небо лезут леса,

турки строят муляжи Святой Руси за полчаса,

а у хранителей святыни палец пляшет на курке,

знак червонца проступает вместо лика на доске..."

Песня "Древнерусская тоска", 1996.

Такие вот дела ;\_(;)_/;

А что ещё по-вашему в сфере русского творческого наследия может оказаться под запретом в случае принятия антинаркотического закона?

…

FPG / Люся Махова - Мама я не могу больше пить

https://youtu.be/IjOAlR36TGs?si=QSzvoTnWX4PRnS-t

Мама Я Не Могу Больше Пить - АкваАри-Ум / БГ+ (2023)

https://youtu.be/wkHdQe2q3uQ?si=OcS1_UVk-ye67Y05

АквА-Ри-Ум Official Video

Мама, не могу больше пить

https://youtu.be/F4vFGFpPfbU?si=CusBWgRmKkNj37dR

Свидетельство о публикации №109061401474